The Zine Culture

PrintWeek India speaks to two of the few Indian visual artists who are championing the print zine movement in India.

20 Jan 2017 | By Payal Khandelwal

The more gargantuan the mainstream becomes, the more there is the need for alternative or counterculture voices to emerge. And one of the key platforms that have hosted many of these voices is independent zines. The first ever association with the term ‘zine’ began with various fanzines for science fiction in the 1920s.

Eventually, zines helped fuel the punk music subculture including the Riot Grrrl movement (an underground feminist movement associated with the punk rock and alternative music scenes) of the 90s, among others. As zinewiki.com (yes, there is a whole Wikipedia devoted to zines) explains, zines have been around forever; they have only shape-shifted a bit over the years.

Instead of being photocopied versions of cutting and pasting of content and images by hand, a lot of zines are now digitally, and sometimes quite finely, produced. Their essence however remains the same in most cases. They are still sold or distributed in small quantities and in selective places. Most importantly, they still champion the DIY, counterculture and personal opinion spirit.

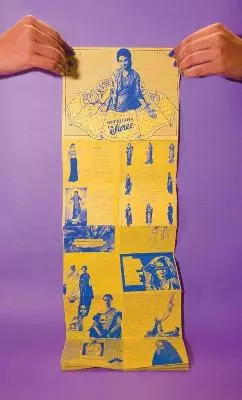

During the last few years, print zine as a medium has been explored by a few Indian visual artists with some terrific results. We speak to two Indian visual artists who have done interesting work in this space and are championing the zine movement in the country. First is Mira Malhotra who has recently created ‘Unfolding the Saree’ – a zine that explores various preconceived notions and cultural implications associated with the saree wearing women in India. Malhotra is also a part of Kadak Collective – a group that includes seven other South Asian women visual artists - which recently hosted a temporary library in Mumbai displaying all their zines.

Then there is Himanshu S of Bombay Underground who first started creating zines independently in the 1990s. Bombay Underground has supported the ‘zine’ movement ardently for many years now - from creating zines to starting an underground library and bookshop in a garage space in Mumbai to now hosting a travelling zine fest starting from 14 January 2017.

Here are the edited excerpts of our conversation with both these artists about their individual projects and the current zine scene in India.

Question (Q): The last few years have seen a huge resurgence in the zine culture in India. What do you think has revived interest in this form, both of artists and audiences?

Answer (A): People are excited about being exposed to new things. They are also getting better acquainted with artists’ and designers’ work. The press is constantly covering this stuff as it’s something fresh. And also, after being bombarded by mainstream media, people are now somewhat resistant to it and are looking for unconventional subject matters.

The idea of zines has existed for a long time abroad, and they have always been self-published and taking unconventional subject matter forward. I think that the graphic novel genre has taken off in India, and zine culture is following on its heels.

Q: What inspired you to work with this particular form (zine+print) for your ‘Unfolding The Saree’ project?

A: I enjoy working on personal projects because working with clients, and being dictated to, can get tiring. I believe that designers can also be authors and change-makers, claiming ownership of their work. This kind of thinking is very prevalent amongst writers, photographers and even product designers but usually the graphic design community believes that design should only be for a client. I don't buy that.

I am particularly a fan of feminist zines and DIY culture, especially of the Riot Grrrl variety which was my first exposure to zines. Self-publishing in India has actually been a big deal but only on digital media. I really value print though for its tactile value. While digital media can be disseminated easily, is cheaper to create, and reaches a wide audience quickly, it’s temporal in nature which is its downside. While it can seek to change an opinion or offer a nuanced side to a story, it can get lost in the ocean of information that washes up on our shores daily. Though each medium has its own strength, and it needs to be applied to different situations.

In my case, it was the culmination of recent incidents and long-term interests that resulted in this zine. I wanted a way to make an Indian version of what I admire about Riot Grrrl but have it resonate with my own cultural experience. I also wanted to build something that's so engaging that the material is not trumped by its content or treatment. I wanted to produce an artefact which can be held, stored, treasured or re-read.

Q: Tell us a bit about your experiences while crafting the zine.

A: Usually, the products created by designers are in limited quantity, and since a lot of craft goes in it, they are often priced highly. I wanted to avoid that by using cheaper, local material. My DIY background and knowledge of printing and its local applications helped me make a budget-friendly product. My ongoing interest in items of 'novelty' like toys found in bazaars and Indian storytelling devices from folk culture also helped. Their interactivity makes for an engaging and innovative experience, and a didactic one (when paired with a facilitator).

I also wanted to make a zine on women and sexuality in some form. Recently, I personally began draping saree, and have been hypnotised by its variety, versatile format, and the way it's perceived (is it sexy? is it modest? does it cover up? or does it reveal?). In an age where we are actively questioning burkinis and bikinis, and what these garments mean to us, it was exciting to look at the saree in this context. Eventually the format of the saree gave rise to the format of the zine. The content talks about several practices including the ghoonghat, the item number, the wet saree, the cover-all saree, nuns wearing sarees, feminists wearing sarees, etc. – all question preconceived notions on the sarees as a dress that can be confined to eternal raunchiness or feminine dignity. The saree is too shape-shifting to be defined as either. This revealing or unrevealing got translated eventually into the words 'folding' or 'unfolding'.

Lastly, I recently joined a collective known as Kadak, which debuted at the East London Comic Arts Festival (ELCAF) this year, and I needed to make products for that. What could be better than to introduce a foreign audience to my own idea of Indian design?

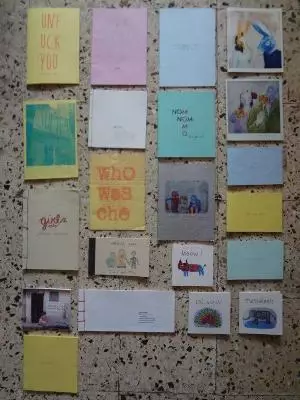

Q: Kadak Collective also recently hosted a library in Mumbai which showcased zines created by its members. What were some of the interesting feedbacks and experiences from that?

A: Our entire idea of having a Reading Room – setting aside a space for reading where we are ourselves present – was great because we could record feedback on comics and zines. There were all kinds of people coming in, those who are familiar with these formats and those who are not. For some people, the idea of comic book content (which makes up the bulk of our library) was very restrictive, only reserved for super heroes and maybe, heroines. But comic storytelling is far larger an art than that. So some of the visitors were surprised by the idea of 'independent' comics, and couldn't understand why it's not like Comic Con.

Also, since we address many gender issues in our works, visitors from certain NGOs could relate to the subject matter but were intrigued and puzzled by the format. Then there were people from media who were quite open. While this was a fairly new format for them as well, they were receptive and engaged with the creations on a far deeper level. To those already familiar with this kind of work, the response was amazing.

Q: What are some of the challenges and the best parts about working on the very tactile print zine form?

A: For Unfolding the Saree, at several points I thought that the format I was dreaming of was too challenging. Firstly, the hangers were difficult to make since I have no experience of product design as such. We eventually got someone who made life-size hangers to create these small hangers from iron wire and then electroplate them.

The other challenge was to make the actual proportions of an average saree in miniature form. I had to make sure that the zine didn’t fluff out too much on the hanger and it had to look somewhat vertically long. That meant 24 folds, and a thick paper was just not going to cut it (pun intended). So we devised it on a local coloured newsprint ‘Belapur colour paper’, which is also budget-friendly. The zine also had to be small while folded but was content heavy inside, so it opens up to a really large size. It's based on the design of an accordion brochure. We devised a sleeve, which is like a saree bag, that helps keep it in control.

Once the prototype was ready, I wrote the content because the format had its own limitations. I used only one colour silkscreen so my printer (William Arts, Mumbai) didn’t have to mix inks more than once. But I did create two patterns and printed on three colours of paper so that it looked interesting in display. I chose colours that were devoid of blue, so that the blue ink would be clearly visible and contrast well. Much thanks to my interns at the time who prototyped and oversaw the printing and my friend Aarthi Parthasarathy (also from Kadak) who gave inputs on the content.

Overall, I see comic makers from film and animation backgrounds struggle with print. Graphic designers have a huge advantage in this area. Still, the knowledge of print process amongst designers is at an all time low because there are so many UI/UX digital designers who have no background in this. So having enough knowledge of print processes is important for a project like this.

Another is finding the capital and time for your own endeavour which involves writing, designing and production. Prototyping also requires some proficiency. Of course, the easiest way to avoid all these is to write and design a zine and just go to town using a photocopier and coloured paper.

Lastly, finding a way to your audience is a challenge. If you don't place the zine in a conducive environment, it won't take off or reach the right people. The best part of a print zine is seeing the physical object, touching and holding it, and preserving it.

Q: What are the specifics, according to you, that truly define a print zine?

A: This is a very difficult question to answer, mostly because there's a very large grey area here. As a given, zines need to be somewhat different or talking about a topic not covered in the mainstream media or addressing/approaching a topic in an altogether innovative way. I think if there's literature which doesn’t have a commercial agenda as such and it's under 1000 copies, you could call it a zine.

I think it also matters where and how it’s disseminated. So you can’t place it in a major bookstore or a hotel lobby because then it’s sanctioned by the establishment and its value as a zine is reduced. Like there are these folded maps you get of Bandra and Versova which are really cute and very zine-like, but nowadays they have so much product placements that they no longer can be called zines.

That said, a lot of people have this notion that zines have to be free but I don’t believe that. They are just not as expensive as a book version of something similar because there's no middleman or extensive reviewing. It goes almost straight from the maker to the audience, with that rawness/freshness preserved.

Q: What do you think has revived interest in zines, both of artists and audiences?

A: Perhaps it is because of an increased exposure to protests and the internet. However, while there is resurgence, most of the stuff is impotent as it’s just riding the wave rather than truly putting something utterly personal out there. We have already seen how street art has failed in this country, although it is celebrated, funded and written about. Let’s hope though that we hear more voices of all kinds.

Q: Personally, what inspires you to work with this particular form and to start an "underground" bookshop dedicated to this?

A: The heart of zine-making has to be rooted in the physical interaction between the zine-maker, zine, and the reader. Zines were meant to be handed over from person to person, physically shared. The experience of holding a zine and turning each page to reveal intimate secrets, funny comics and poetry can’t be duplicated online. You would get the content, but miss out on the physical experience. In the age of tech, social media, and instant access to anything and everything, these help slow us down in a good way.

I started ‘Underground Bookhouse’ with my partner Aqui Thami (who also makes zines) and with the help of a few friends. It’s hard to find library materials that challenge the for-profit, corporate culture. Our well-stocked public and university libraries, though publicly funded, primarily serve private middle-class constituencies.

There is a clear gap in the information world. It is very hard to find any materials published outside the mainstream, and especially hard to find materials that have been self-published (zines and factsheets), or non-mainstream periodicals, newspapers and tabloids. We needed more independent bookstores in the city, and we took it upon ourselves to fix this. We have all dreamt of owning a bookstore, and this is the time to make it real. This is a bookstore owned by booklovers, and we are inviting more people to help sustain the space.

Q: What are some of the specific challenges and the best parts about working on the very tactile print zine form? You also give complete freedom to people who contribute to the zines, practicing little editorial control. Tell us a bit about that as well.

A: Sustaining the making of these zines for so long has been a struggle but a sweet one. I first started making leaflets and booklets in 1998-1999, and a lot has evolved since then. A lot of grassroot counter-culture movements in the city have either given-up or mellowed down, and everything has become more shiny and polished. Fortunately though, our zines in their minimal form still help us connect with the very few but really interesting people.

About the little editorial control, it is fun to put together a wide range of things and therefore enjoy a varied range of readers and admirers.

Q: What are the specifics, according to you, that truly define a print zine?

A: For me, zines are always stronger when physical. And all that is utterly personal is bound to be counterculture in today’s messed up times. This could be the simplest defining element for a zine, if there has to be one.

See All

See All