A journal for young children who the world has passed by - The Noel D'Cunha Sunday Column

Apple Press painstakingly created with handmade paper and personal attention. PrintWeek talks to Tansy Troy and Dikshit Sharma, to understand how they produced the book, but more importantly about the importance of education in these tough times

05 Dec 2021 | By Noel D'Cunha

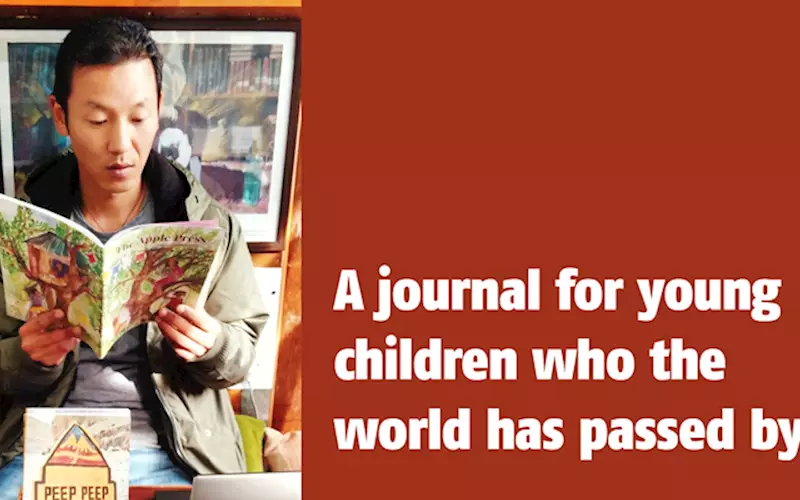

We have written in these very pages how the pandemic has been especially hard on the children from underprivileged backgrounds. We have also written about people and organisations who are fighting to overcome this. One such example is The Apple Press, a young people’s journal, edited by Tansy Troy, and designed by Dikshit Sharma, which was dreamed into being in the midst of Manali orchards when physical resources were needed for young people in remote Himalayan communities during the educational lockdowns.

Printed on khadi paper and bound by hand, rich in stories, poetry, photographs and illustration around five themes — star, creature, bird, tree and earth, the first issue of The Apple Press is now out. And, for every copy of The Apple Press purchased, another is gifted to a young person with limited access to technology and educational resources.

The magazine was printed on handmade recycled rag paper by Delhi’s Khan Market-based iconic Anand Booksellers and Stationers, and was hand-bound by the expert needlework of the Karigar community.

Launched in October 2021, Troy and Sharma are taking this inaugural issue to the young monks of Zanskar’s remote Phugtal monastery, the street seller kids of Manali and the da Hanu tribe children of Ladakh, where the copies of the magazine will be distributed for free.

Excerpts from an interview with Tansy Troy and Dikshit Sharma

PrintWeek (PW): Congratulations on the inaugural edition of Apple Press. The issue looks solid. What is your work method?

Dikshit Sharma (DS): We are taking it slow, embracing it all for a deeper understanding and connection with audience, readers, viewers. Letting things flow without limits, using a diverge and converge method.

Tansy Troy (TT): We have been exceptionally lucky with the inaugural edition of Apple Press. The generosity of the artistic community has been second to none. Our ‘work method’, if indeed we have one, is to keep reaching out, keep communicating, work like the blazes and love every moment. It’s been great to showcase well-known artists and writers alongside newcomers, usually children. For me, this has kept the content on its toes.

PW: The reaction of the young monks at Phugtal monastery in Zanskar?

TT: Sadly, we have not reached them yet! Just before their workshop leader Rinchen Kalsang and his team arrived, heavy snowfall in Zanskar stopped play, blocking all routes to Phugtal. Some senior lamas from Phugtal, who were in Manali, blessed our zoom launch with their prayers and have since been seen in the local bookstore, heads deep in copies of Apple Press. Now that weather has somewhat shaped our time-frame, we have decided to take an even bigger crew to Phugtal next Spring when the passes open.

PW: The response to your storytelling by the pavement school street kids who usually sell balloons, etc?

TT: This has been one of the greatest eye-openers of the entire project so far. My expectation was that a journal in English, however richly illustrated, may have slightly limited appeal for this particular group of young people. The attention and focus of the Nepali refugee and pavement school students, from the beginning of the (bilingual) story to the finishing of the last bird puppet and prayer flag, was nothing short of outstanding, making me realise how seriously our less-advantaged students take creative opportunities.

PW: Also, what has been the response to Dikshit journeys in Shantiniketan and Kalimpong with the journal?

DS: In Shantiniketan, I showed it to an artist friend from Turkey and she and her friends are inspired to contribute to the next issue. I also took Apple Press to a famous bookstore in Darjeeling and they may be interested in stocking some copies.

PW: One response in Manali that triggered your imagination?

DS: The changing of the orchards from snow-covered bare branches to fruition.

TT: An illustrator who works for the Natural History Museum in London and is also a sometime resident of Manali, wrote us an email. He had picked up his copy of Apple Press in Bookworm and so enjoyed it that he sent a plethora of fine illustrations for us to use in the next issue. Seeing such beautiful work inspired a thousand thoughts for new stories!

PW: Which are you working on next?

DS: As well as the next edition of AP, a book documenting the life and times of the last tribal queen of Testa Kha (Zanskar). This visual narrative hopes to be a book that will accompany a photographic exhibition in Zanskar.

TT: The next issue of Apple Press! And an artist’s book of poetry about each of the nine rasas, illustrated with abstract paintings by Dikshit.

PW: Your first memory of a book?

DS: Hmmm... images that are coming to me when I think back are of going through these huge encyclopedias we had. Even though I wouldn’t understand much, I would go through the pictures and visually grab information.

TT: For me, a stunning if ragged first edition of Mary Cicely Barker’s Lord of the Rushie River. As a five-year-old, the illustrations (colour plates and line illustrations) completely fascinated me. I remember being shown this lovely little book by a very impressive and aristocratic friend of my mother’s, who was perhaps a relative to either Edith Sitwell or Winston Churchill. We met her in London and she was in love with a dashing and completely alcoholic young Russian. I have a sensation to this very day of escaping into the solace and refuge of this beautiful book while the adult world of desperate romance and adventure went on above my head.

PW: One book in school / college that was taught awfully?

DS: History books, mugging up facts and memorising without any interest.

TT: Racine’s Phedre, at Cambridge. Ever since, I have only ever heard great things about this classic. At the time of reading, it was droned out in dirge-like verse enough to put you off French for life.

PW: One book that changed/shaped your view of Literature?

DS: Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert M Pirsig.

TT: Too difficult: it will have to be no less than three complete works. When I was travelling around India with my mother as an eleven-year-old, I insisted on taking the complete works of Shaw, Wilde and Shakespeare on every epic train journey we went on. These gigantic tomes no doubt properly annoyed the many station porters obliged to carry my travelling library on their heads: but they informed and shaped my understanding of English literature ever after.

PW: What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given in your journey?

DS: More than advice I guess it’s the collaborative effort, discussing and brainstorming ever changing ideas together that’s been as helpful as any good advice.

TT: Advice from Dikshit, actually. Start small.

PW: One living author who you would love to write for your next book?

DS: Most are dead but I do want Banksy to send in an anonymous contribution!

TT: So many, so hard to choose just one. May I have three? Arundhati Roy, Mark Tully, and Jerry Pinto.

PW: One writing quote that you love to quote?

DS: By Henry David Thoreau: “The question is not what you look at, but what you see.”

TT: Let’s have one for Apple Press from William Butler Yeats’s ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’: And pluck till time and times are done/The silver apples of the moon/The golden apples of the sun.

PW: One tip for others who want to replicate the AP story telling sessions?

TT: Keep it live, make your own props and puppets, involve your audience with genuine interest, offer skills to support their own storytelling.

PW: Message for the print and paper industry (if any)?

TT: Be as eco as possible: think recycled paper, plant-based inks, believe in the printed word: it lives on.

Educating children during the pandemic

PW: While physical schools are closed, online classes seem to be going on, via smartphones, through audio-visual media. How do you think the introduction of these online teaching methods has affected the holistic development of a child?

TT: Having just returned to on-campus teaching after a year-and-a-half of online classes, we can definitely say this electronic style of teaching has affected both teachers and students so profoundly that we are all having to re-learn how to be together in a room, how to be a group, a community. Children began by displaying behaviour which translated as a kind of starvation for tactile resources! Things are being played with back in the classroom as never before. Most seem less familiar with books than before, another re-learning. Fine motor skills are less refined. Feels like a long educational haul ahead.

PW: In a country like India, a majority of the population still don’t have access to the internet to access these online classes. What happens to these children? Do they miss out on their education for a whole year and can there be something done about it? As someone involved with children’s literature, what is the solution to this problem? Community libraries can be an answer.

TT: Have been reading marvellous things about community libraries. It feels like a prime time for potential for new resource banks, alternative centres for education, arts centres, to start putting down or deepening roots in India. Unlikely groups have been locked down together and new projects (like Apple Press) have been born as a direct result, along with so many other creative ventures.

PW: How has the pandemic affected the work in your organisation and how are you dealing with the fallout?

TT: Creative and divergent thinkers tend to experiment and try out new ideas at times of apparent disaster and during the breakdown of ‘normal’ social structures. So, the fallout can actually be translated as a moment to shape things anew.

PW: How do you see the future for children’s literature?

TT: In answer to the second part of the question, I feel there is a renaissance going on in children’s literature in India right now. It’s a totally exciting time to be working with young people and in young people’s literature. Science is teaching us so much about the way we best learn; and here in India, there is such a huge, deep, rich tradition of art, music, literature: finding ways to introduce this vast wealth to the younger generation is an enormous honour and beautiful journey to be on together.

See All

See All