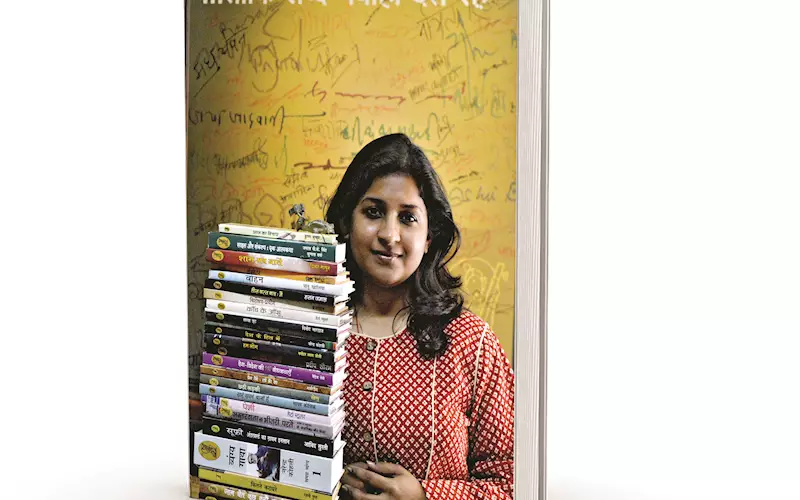

With half-a-century of experience and expertise, Delhi-based Hindi language publisher Vani Prakashan boasts a catalogues of more than 4,500 books. Aditi Maheshwari, the third generation of the publishing house, explains to Dibyajyoti Sarma and Rahul Kumar why books are still relevant in India

Do not listen to naysayers. Books are doing well in India, even the regional language ones; especially the regional language ones. It is more so in case of Hindi, our national language.

One such example is Vani Prakashan, which, in its 51st year, has achieved a pre-eminent position in the world of Hindi publishing through its list of more than 4,500 books.

Make no mistakes; Vani is not your run-of-the-mill publisher of popular trade paperbacks. It is much more ambitious. It has a global vision within the context of a local language. When we visited the publisher’s office in Daryaganj sometimes back, we met a Japanese woman who is translating Japanese Manga comics into Hindi for Vani Prakashan. This exemplifies clearly the reach and ambition of Vani, which is engaged in bringing home world literature to the confines of the national language.

“We work with international bodies like Goethe Institute, Pro Helvetia, Alliance Françoise, Polish Book Institute, NORLA, German Book Office, and so on, to translate a wide range of international literature directly into Hindi. Authors like Nobel Laureates Czeslaw Milosz, Zwigniew Herbert, Wislawa Szymbroska, Tadeusc Rozewicz and Herta Müller and authors from France, Austria, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Poland, Romania, America, etc are the proud entries in our list,” says Aditi Maheshwari, the third generation publisher of the company.

While striving to bring out the ‘cosmopolitan’ nature of Hindi literature, Vani is also shedding light on the important Indian literary movements, and has consequently published authors of Dalit, feminist and adivasi discourses extensively, she adds.

We come to the point. In the recent years, we have seen publishers complain that books, especially physical books, do not sell anymore. Is this the reality? Maheshwari gives a detailed answer. “The aesthetics of a book encapsulates engagement with ideas and their logical development. They will always remain at the core of any socio-political or personal ecosystem. However, with innovations in technology, the forms and medium involved in reading have diversified,” she says.

Coming to the question of printed books, Maheshwari says they will never go out of fashion. The demand for books, not only in India but everywhere, will never go down. “The printed books will be read along with, if not as a substitute to, the digital and audio books,” she adds.

According to Maheshwari, it is an exciting phase for Vani Prakashan, as new genres, writings and readership has unfurled in the last decade. The advent of web applications, rise in per capita income, social mobility and so on, have contributed to this change.

She should know. So far, Vani Prakashan has published more than 4,500 titles, of which about 18-20% constitutes the bestselling and fast-selling list. “We produce more than 225 books each year. It’s like saying ‘good morning’ to a new book on our table each working day,” she says.

However, when it comes to market share, she declines to come up with a number. “It is difficult to talk about market share because we are essentially a data deficit industry in a hugely data deficit country. By approximation, we should be among, if not the one, top producers of Hindi books in the country,” she says.

What constitutes a bestseller? Maheshwari says if a book sells about 5,000 to 7,000 copies in the first two years of its publication, it is considered a best-seller. “However, I personally feel we cannot imbibe a TRP kind of model to understand the cultural economy of books. Each idea (and the book) lives through its own life cycle. One cannot judge a book by the number of copies it sells, and likewise no language should be judged by the number of best-sellers written in it,” she argues.

For example, Vani has sold more than 5,00,000 copies of Lajja by the Bangladesh author Taslima Nasreen and about 1,00,000 copies of Ma by Munawwar Rana. At the same time, it also sells not more than 500 copies of a poetry collection and maybe, a few couple of thousands of a non-fiction book. “But, all the books remain close to us and their readers. We give each one the best of our editorial, marketing and sales operations,” she says.

Reaching the readership

And, how do these books reach their readers? Maheshwari explains, “Our sales team is one of the most dynamic in the industry because it is trained in dealing with multiple portfolios at the same time. I think we are unique because we welcome a giant online or a brick-and-mortar distributor, or a tiny bookstall owner with equal aplomb and interest.”

With the so called tiny bookstalls slowly shutting shops, and with online retail taking over the sale and distribution of books, Vani sells its books through its own website and through other online bookshops. “The online book market, at least for Hindi, is not as big compared to the offline market. However, it has become important to have a strong publicity programme and a prominent presence online because it directly affects the offline sales,” Maheshwari explains.

How about eBooks in Hindi? While eBooks right now is a legitimate branch of publication for English language publishers, in case of regional languages, there is still a lot to be done. “The eBook configurations for Indian languages have taken a lot of time to catch up with international digital rights management systems. This is primarily because the international market has undermined the market of literatures in Indian languages, and thus, the lopsided research and development in the area,” Maheshwari says.

A recent report showed that whereas Kobo and Google Books have been supporting text in Indian languages, Kindle has not listed them at all. In fact, Kindle supports Turkish, which has far less speakers compared to Hindi. On the other hand, portals like Newshunt.com are doing a good job in promoting and selling Hindi eBooks.

Quality control

Earlier, Hindi trade publication was equated with cheap printing, wasn’t it? Maheshwari begs to differ. “I think it is a myth that Hindi books are of low production quality, propagated by the ones who have engaged with them only with an external gaze. Hindi books have had excellent production quality,” she says.

And even local language books are no longer cheaper. Unfortunately, however, the cost in cover price has not benefited the author, the publisher, or the reader because of the subsequent increase in the discounts demanded by distributors and booksellers, says Maheshwari. “The distributors and booksellers in turn have high establishment costs. I sincerely wish we learnt something from the European Fixed Pricing Law, much strengthened by the German Publishers and Booksellers Association. The law puts to practice the regulatory mechanism in fixing prices of books, which solves many problems in the ecosystem,” she adds.

When it comes to quality of books, printers play an important role. “It is a delight to work with educated printers who are also good readers,” says Maheshwari, adding, “Though they are rare these days. We get paper samples from merchants spread around Old Delhi. We do receive suggestions on paper quality by experienced printers. The digital boom in printing has helped Indian languages improve their quality. Although it is desirable to have cheaper four-colour and eight-colour printing solutions, the progress so far has been satisfactory. Vani Prakashan publishes extensively with the digital and offset medium on a parallel ground.”

Reading Hindi

Maheshwari says the Indian publishing market is estimated to be an Rs 10,000 crore industry. It is essentially the most exuberant publishing landscape in the world with 24 Indian languages, of which many have a thriving print and public culture of letters. According to FICCI, more than half of the total titles published in India are in Hindi and English, with Hindi constituting about 26%, followed by English at 24%.

Hindi being the official language of the country also helps. It has readership all over India. “It might surprise many, but Hindi is as popular in Kerala as it is in Patna,” Maheshwari says. On export of Hindi books, she adds that the numbers have declined in the last few years. “The Diaspora of the Hindi heartland has not explored their literature as much as the Bengalis or Malayalis have done,” she says.

How about government help? Maheshwari says the government has not expanded its role beyond providing grants in facilitating purchase of books for educational institutions. “It must understand that the publishing industry needs urgent attention in the arena of policy making. It is quite surprising that despite the fact that all presidents and prime ministers of India have been avid readers, yet they have not paid attention to the trade that produced all those books they loved reading. The government must engage the youth in the publishing industry on the basis of merit and expertise to bring forth and overcome the lacunae,” Maheshwari argues.

Talking about the future, Maheshwari says while it is an exciting phase with respect to content, it is also a stressful time with respect to policy and logistics.

“It needs an amount of madness and undying passion to be in the Indian book trade, especially of an Indian language,” she adds.

Of course, ‘once a publisher is always a publisher’. “It is a dream come true each time I hold a new book that Vani Prakashan produces,” Maheshwari concludes.

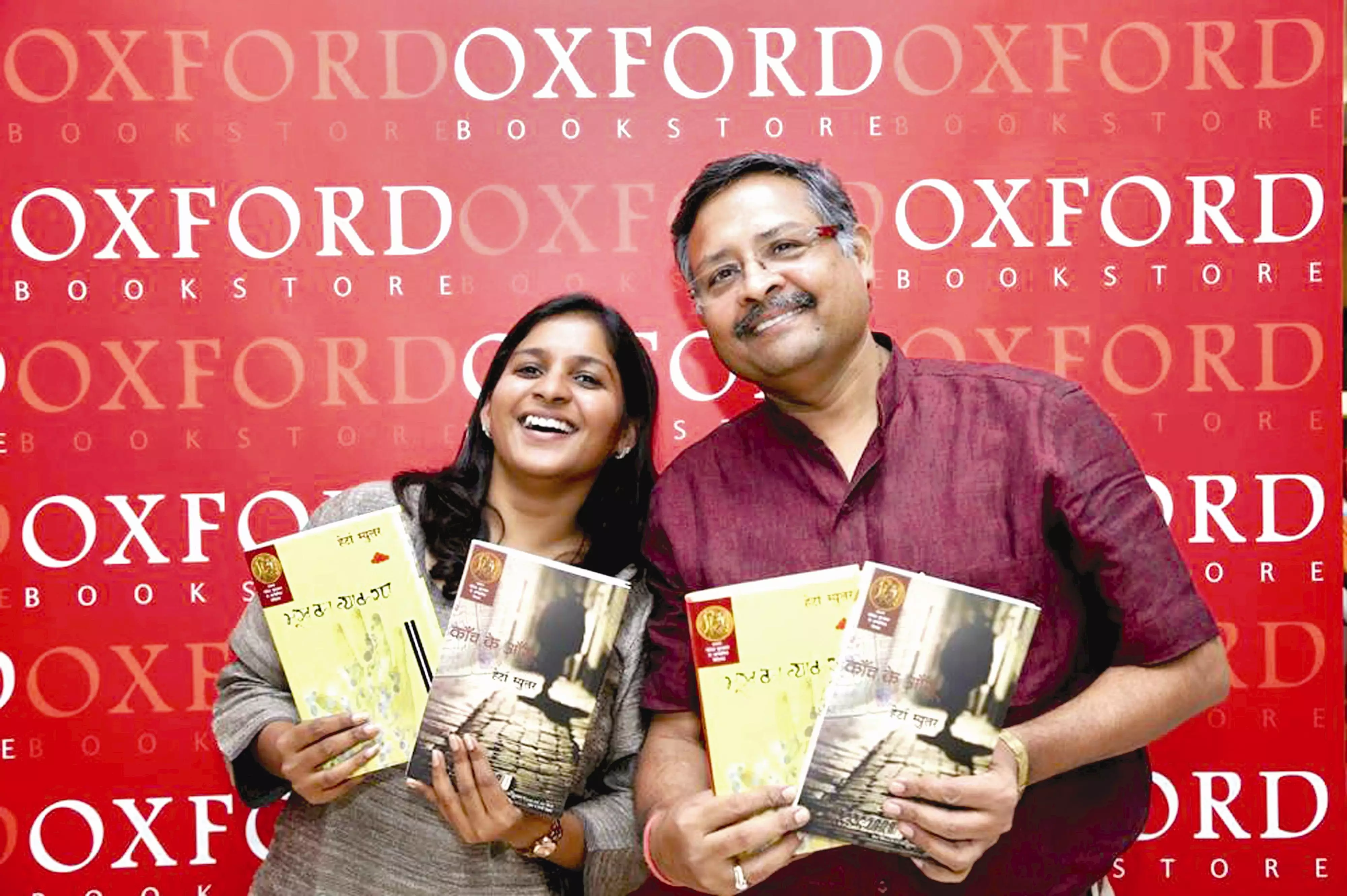

During the launch of the Hindi translations of two novels by German Nobel Laureate Herta Müller

During the launch of the Hindi translations of two novels by German Nobel Laureate Herta Müller

“We work with international bodies like Goethe Institute, Pro Helvetia, Alliance Françoise, Polish Book Institute, NORLA, German Book Office, and so on, to translate a wide range of international literature directly into Hindi. Authors like Nobel Laureates Czeslaw Milosz, Zwigniew Herbert, Wislawa Szymbroska, Tadeusc Rozewicz and Herta Müller and authors from France, Austria, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Poland, Romania, America, etc are the proud entries in our list,” says Aditi Maheshwari, the third generation publisher of the company.

“We work with international bodies like Goethe Institute, Pro Helvetia, Alliance Françoise, Polish Book Institute, NORLA, German Book Office, and so on, to translate a wide range of international literature directly into Hindi. Authors like Nobel Laureates Czeslaw Milosz, Zwigniew Herbert, Wislawa Szymbroska, Tadeusc Rozewicz and Herta Müller and authors from France, Austria, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Poland, Romania, America, etc are the proud entries in our list,” says Aditi Maheshwari, the third generation publisher of the company.

See All

See All