Journeying with children’s books

Vinutha Mallya, publishing pundit, charts the path of children's publishing in India since Independence.

13 Oct 2015 | By Vinutha Mallya

One of my all-time favourite books is A Visit to the City Market by Manjula Padmanabhan.

Published by the National Book Trust, India, the story is simple: Two siblings set off to the market with their mother. The beauty of the book is that we read it visually, because it has no text. Before we close the slim book, we finish a walk with the children and see what they’ve seen with their curious senses. It is easy to become an inquisitive child while reading this book.

We often relegate children’s books to a basket we call ‘learning’ – an imposition of school curriculum, or morals, traditions, religion, etc. Very few adults think of them as windows that open up the imagination of the mind.

Because our focus has been on improving literacy, since Independence, the link between school-based learning and reading has been strong. Efforts in publishing children’s books are largely focused on school-related books. But a good number of books for leisure and pleasure-reading are based on religion (mythology), culture, traditions and moral values, and aiming to control the shaping of the child's mind even before they are able to grasp the complexity of these concepts. There are also those books that are mere imitations of what is produced in the West. But a small number of book publishers have moved away from this and have created a language for books that focuses on, cognitive development and exploration of creativity.

The children’s book segment, which is not textbooks, is one of the fastest growing segments in the publishing industry. While statistics from India are hard to find, growth in the more developed markets is between 12–15%. The rate is more likely to be higher in India because of the growth in literacy and better purchasing power among people. But, publishers in India have been producing children’s books since long, before it emerged as a lucrative segment.

The old guard

The old guard

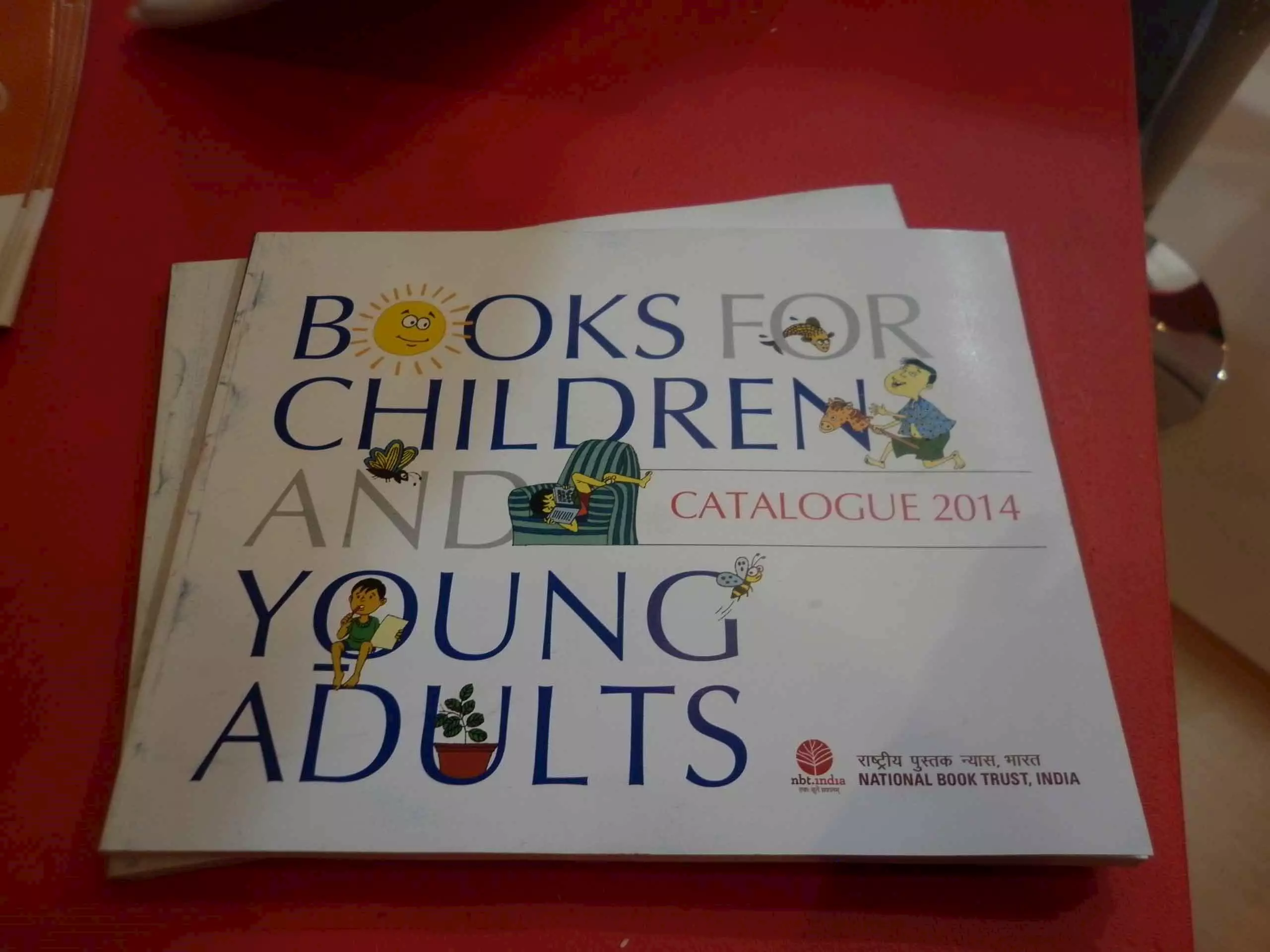

The Children’s Book Trust was one of the first to produce illustrated and picture books for children. It was set up in 1957 by the cartoonist Shankar in New Delhi. CBT commissioned well-known artists and illustrators to create visually rich books in different languages. It also set up the Indraprastha Press in Delhi, and its books were distributed across the country. Drawing inspiration from CBT’s work, the National Book Trust, India started publishing illustrated and picture books for children, just a few years after it was founded in 1957. Just like CBT, NBT also took on well-known writers and illustrators of the time. Many of the books produced by CBT and NBT remain in print and are available across India.

Through its multilingual publishing programme and because of its mandate to produce and make available affordable books, subsidised by the government, the National Book Trust has played an important role in the reading habit. Through book fairs, mobile vans and by organising the New Delhi World Book Fair, the NBT ensures that affordable books for children reach the length and breadth of the country.

Even outside the capital, efforts to produce books, especially in the Indian languages, were strong in the states. The Shishu Sahitya Sansad began publishing books in Bangla in 1951. In Gujarat, the Navbharat Sahitya Mandir published many cult book series in Gujarati for children, like Chako Mako, Miya Fuski and the goat-detective Bakor Patel.

Readers would recall periodicals like Chadamama, Champak and Amar Chitra Katha, which were published simultaneously in various Indian languages. These, and magazines like Kishor (Marathi), Sandesh (Bangla), Chakmak (Hindi), Mouchaq (Asomiya) and Target (English), were instrumental in instilling a love for reading. Soviet books, then known for their quality of production and variety in subject matter, were once easily available in India. The efforts of groups like the erstwhile Makkala Sahitya Academy, in Karnataka, focused on encouraging children’s book writers, by conducting workshops, meetings and seminars. The public library system and book fairs gave wide access to books.

The young Turks

The young Turks

New publishing houses came up in the mid- and late 1990s, after the liberalisation of economy. Katha Books, the translations publisher in Delhi, which started publishing in around 1988, began publishing children’s books. The three Chennai-based houses – Tara Books, Tulika Books and Karadi Tales – were set-up in the mid-1990s. They helped launch a unique language for Indian books, which focused on Indian stories and storytellers, as well as on good production quality.

Each of the publishing houses carved a niche: Katha specialised in translations, Tara in fine bookmaking technique, Tulika in bilingual picture books, and Karadi in complementing books with audiobooks. Some books produced by Katha and Tulika are a part of the CBSE’s recommended reading list. The Bhopal-based NGO, Ekalavya, launched its children’s books programme in 1996, which produced books in Hindi and other languages, such as Mundari (a tribal language) recently. They launched with support from Sir Ratan Tata Trust and the Ministry of Human Resources Development.

Puffin, Penguin’s children’s books imprint, created a selection of well-produced English books for children. The company’s distribution prowess helped the books gain greater visibility in bookshops in the cities. The American publisher, Scholastic, came with a strong list of titles and marketed them aggressively through schools. The company then began to also locally commission books.

Towards the mid-2000s, newer entrants came into the field. Young Zubaan, an imprint of the feminist publishing house, Zubaan, was launched to produce inclusive books for children. The not-for-profit Pratham Books started out with the vision to put a book in the hands of every child, and it has since produced books in different Indian languages. The organisation broke convention in many ways. It heavily used technology and social media to promote its activities, and it also introduced Creative Commons licensing in trade publishing. Pratham’s costs for developing its books are covered by philanthropic donations it receives while the distribution of books is funded from book sales.

The growth of children’s books and young adult segments worldwide has triggered the launch of several imprints in India in the last 3–5 years. Kerala’s largest publisher of books in Malayalam, DC Books, set up the Mango Books imprint in English. These books do well in the Gulf countries. Now, there is also Rupa’s Red Turtle, the children’s books imprints of Hachette and HarperCollins, and the independent Duckbill, which publishes books for young readers and young adults. New companies are mushrooming.

In the comics segment, Campfire has succeeded in creating a brand with a good export base. The old favourite, Amar Chitra Katha, is repackaged, repurposed and is available in animation.

Making books travel

Licensing of content remains the best way to make books travel to other territories. Among the Indian children’s books publishers, Tara Books has seen good success in licensing their work. Any publisher serious about making their books available outside India cannot miss the annual Bologna Children’s Book Fair in Italy. Other international book fairs, like in Frankfurt and London, are also important meeting places to find potential partners, to sell as well as procure licences. The Rights Table at the New Delhi World Book Fair is growing in participation from many countries.

Licensing of content remains the best way to make books travel to other territories. Among the Indian children’s books publishers, Tara Books has seen good success in licensing their work. Any publisher serious about making their books available outside India cannot miss the annual Bologna Children’s Book Fair in Italy. Other international book fairs, like in Frankfurt and London, are also important meeting places to find potential partners, to sell as well as procure licences. The Rights Table at the New Delhi World Book Fair is growing in participation from many countries.

Founded by the German Book Office in New Delhi, Jumpstart, the congress for children’s content, has helped invigorate thinking about content for children, at least in English. The canvas for creation and delivery of content has expanded due to new technology. At the same time, the revival of storytelling among the well-to-do segments of society in a city like Bengaluru shows that the tried-and-tested methods work.

For Indian books to truly travel, among readers in India as well as abroad, we must look at the substance of our content. The religious as tradition, the rural as folk, the kitsch or Western as modern, even the obsession with the back-to-roots phenomenon – these clichéd representations ought to go. Fresh ideas, rooted in our diverse and secular ethos, is what we must focus on.

More needs to be done to make books travel within India. Localised content creation is one way to generate books within communities. Children not living in the metros and larger cities must be able to dip into the stream of stories that surround them as well. A strong library movement, many points of access, and wider sharing of ideas, this is what children’s books need today.

During the Bengaluru leg of Jumpstart this year, the Australian writer Leoni Norrington reminded us: “A good story is never didactic, never preachy – the real story lies underneath all that.”

See All

See All