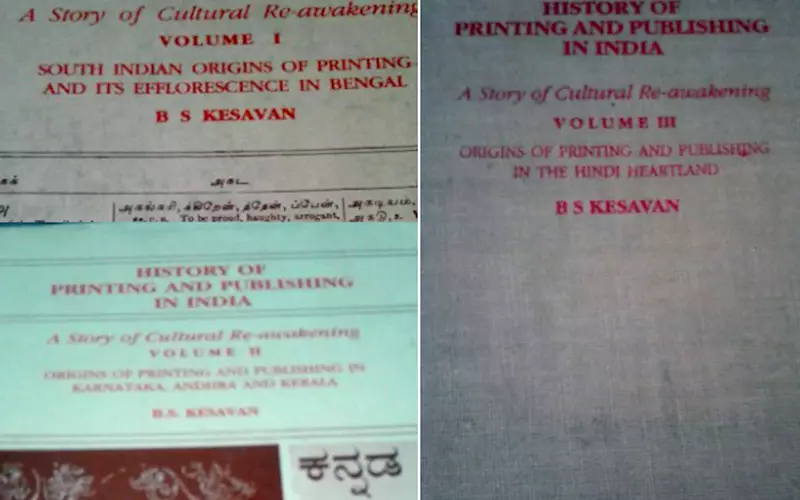

On BS Kesavan’s History of Printing and Publishing in India, Volume III

Som Nath Sapru reviews History of Printing and Publishing in India, Volume III: Origins of Printing and Publishing in the Hindi Heartland by BS Kesavan.

13 Mar 2019 | By PrintWeek India

Way back in late 1997, during the World Book Fair in New Delhi, a leading newspaper published from Hyderabad, while reviewing the annual Fair, wrote, “Indian printing/ publishing is one of the most underrated intellectual enterprises in the country.” I wish the commentator had gone through BS Kesavan’s three-volume monumental work before making this comment.

On my recent return flight from the US to New Delhi, I did go through with one of my prized possessions in my small collection of reference books on printing/ publishing in India — the third volume of Printing and Publishing in India: A Story of Cultural Re-awakening (Origins of Printing and Publishing in the Hindi Heartland) by BS Kesavan.

Bellary Shammana Kesavan, born in 1909 and educated in Mysore and London in English Literature and Library Science, worked as chief librarian of National Library, Calcutta, from 1947 to 1962, after being the educational advisor in the ministry of education, government of India from 1946 to 1947.

I am thoroughly convinced that Kesavan has proved that newspaper comment was rather shallow, as he successfully presents a subject like printing/ publishing in scholarly way — a perfect and delightful treat for the intellectual mind. The author’s professional librarian’s skills and intellectual background are visibly evident in this well-researched tome.

As known, printing in its modern sense was introduced in our country in 1557, while the development of printing and typography in several languages of our rich and varied land has progressed side by side with the growth of our publishing. A great part of our culture, past and present, is synonymous with what has been written and recorded in the books produced in several languages in our country.

The book in review starts with philological analysis of the word Hindi, with investigative references from the works of European and Indian scholars. It includes brief comparative references about the origin of Hindi and Urdu and how religious renaissance influenced the development of Hindi and Urdu. It also includes descriptive chapters on the initiatives of early East India Company officials and British bureaucrats for adapting Hindi as an important tool for the organisation of administration in Central and Northern India.

At the time of introduction of the Charter Bill in 1833 for the creation of Western Provinces with a separate Presidency and a Governor over it, yet another change was introduced in the administration of revenue. That was the adoption of Hindi language in place of Persian as the medium of official transaction. The then Secretary of Board of Revenue issued an order on 29th July 1836, and wrote, “All the oral communications of the revenue officials of every class with the people are in the vernacular dialect and it is obviously desirable that all the records and the written communications should be in the same language similarly intelligible to this great body of people.”

This change started in Central India first where Devanagari script and Hindi was universally in use. So this initiative of the early British administrators was commendable in the progress of the language.

A milestone and a creditable effort by early British administrators in the field of development of Hindi were the compilation of a Hindi Dictionary and writing of a Grammar by Dr Frances Balfour Gilchrist and Kirkpatrick in 1785. Although the project was held up as the Devanagari types were being designed and cast, finally the whole work was composed in Roman characters.

By 1805, Devanagari type was ready and less than five hundred copies of St Matthew’s Gospel were printed, followed by A Grammar of Mahratta Language. Later in 1813, John Shakespeare’s A Grammar of the Hindustani Language was printed by moveable types of Devanagari and Persian in London and this book was used as an instructional manual to teach Hindustani (both Hindi and Urdu) to the East India Company officials and British traders. Several editions of this book were printed and in its last edition in 1843, a short grammar of Dakhani was also included.

Kesavan has documented the early attempts of several western enthusiasts in the field of developing, designing and making commercially viable Devanagari types right from 1625 to 1796.

Kesavan claims that the first appearance of Devanagari in a newspaper was in an official notice in the Calcutta Gazatte in June 1796. The first casting of Devanagari types for the commercial use was done for Wilkins at the Caslon Foundry in London and the same types were used by Raja Sarabhoji II’s private press for the printing of Sanskrit and Marathi works.

Kesavan’s documented description of evolution of Devanagari typography from the time of Prof Gaspare Gorresio’s first edition of Valmiki Ramayana, which was printed in 1843-67 up to Tukaram Javiji’s 1901 edition of Tulsidas’s Ramayana is an eye-opening study for any reader and a delight for the connoisseur of good literature. The author stresses that “the Devanagari series 155 in 12 point, designed and cut as early as 1923 is considered to be the finest oriental and most important Indian script ever produced by the Monotype Corporation.”

European penetration of the Indian Ocean gave a boost to the development, designing and printing with the moveable metal types. The first printing press in India was set up by Portuguese Jesuits in Goa in 1556 but the earliest printed specimens of Devanagari are in books produced in Europe.

Concentrated and calculated activities of missionaries with the patronage of the East India Company initially and later by the British Raj administrators gave a boost in the establishment of printing presses in India, which also reflected in the development of other regional language scripts besides Devanagari and Urdu. The interest in indology in the continental Europe also gave a boost in the development and design of Devanagari types, which led to the casting of excellent designed types. The first Sanskrit text printed in Bonn in 1823 was edition of Bhagvad Gita, which was immediately followed by Hitopadesha in 1829.

It’s admirable the kind of efforts put in by the author in the compiling of this volume and bringing to the notice of the scholars most important milestones in the history of development of Hindi language and its Devanagari script and opining that how crucial it is to have one script for all regional languages which will be a permanent binding glue for much needed total national integration.

At the same time, the contribution of the entrepreneurs like Nawal Kishore Bhargava, Chintamani Ghosh, Sarabhoji and scores of Jesuit missionaries, who started printing presses in Central and Northern India in establishing early printing presses is admirable. The initial work in the printing of scores of books by Nawal Kishore Press, The Mustafai Press, Gazette Press at Delhi, Orphan School Press at Mirzapur, Cawnpore Press at Cawnpore and up in North Lodehana Press at Ludhiana started by a missionary is commendable. These printing establishments printed scores of books besides government papers and circulars.

Kesavan, who was awarded the Padam Shri, has successfully brought forward the socio-political developments along with the subject and made it an interesting and readable volume. This book is an ocean of information for students and researchers in the field of publishing and journalism. The facsimile reproduction of several selected pages and covers of some rare books is really a treat and superb tool for the observation of the evolution of design and development of a script, language, and the methods of reproduction.

See All

See All