Print History: A print job in Tibet - Narthang Monastery Press

Getting a book printed in Tibet, the ‘roof of the world’, had its own special challenges. A Hindi travelogue from the 1930s describes the arduous experience

31 Oct 2023 | By Murali Ranganathan

Of all the regions abutting India, Tibet can claim to have the longest print heritage which can be traced back to the early seventeenth century. Sandwiched between two very prominent cultures, Tibet imbibed the best they had to offer. The most important Indian export was Buddhism which underpins an entire way of life in Tibet. From China, came technology of every kind including paper and printing. The Mongols also played an important role in the political and cultural life of Tibet until the mid-1600s. With the ebbing of Mongol power, China dominated the political discourse in Tibet until, in turn, it was displaced by the British empire in the early twentieth century. Throughout this period, Tibet was a Buddhist theocracy with varying degrees of independence.

Because of its remote geography and extreme climate, travellers visiting Tibet had to combine a strong sense of purpose with ample resources. They also had to overcome the deep-rooted suspicion of British hegemony which had induced the Tibetan government to discourage, if not debar, foreigners from entering Tibet. But Tibet was not completely closed to the world. Newari traders from Nepal were a prominent presence in Tibet for centuries, especially along the trade routes. Monks from Bhutan, Ladakh and Kinnaur, regions within the Tibetan sphere of influence, routinely stayed for many years for advanced Buddhist studies. There were spies galore who entered Tibet under various pretexts. For example, Saratchandra Das, who began teaching at a Tibetan school in 1874, was also an agent of the British empire for decades. And then there were the professional travellers.

One such aspiring traveller was a native of Azamgarh (in modern Uttar Pradesh) who, by the 1920s, professed a deep interest in Buddhism. Born in 1893 as Kedarnath Pandey, he had been on the move since his teenage years, sampling various sects and religions. Acquiring a new name every few years, he had already travelled the length and breadth of India. His current appellation was Baba Ramodar. Turning his attention to Buddhism in the mid-twenties after a visit to Ladakh in 1926, he had spent the next two years in Lanka learning the Pali language and Buddhist philosophy at the Vidyalankara Pirivena. And, by 1929, he was hoping to go to Tibet so that he could spend five years in Lhasa studying Buddhist religious texts which were no longer available elsewhere.

The thirteenth Dalai Lama (1876–1933)

The way to Lhasa

Ramodar had read the two books which recent travellers had written about Tibet. Alexandra David-Neel, a long-time practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism, entered Tibet via China in 1924; her travelogue, My Journey to Lhasa, was published in 1927. Even earlier, Three Years in Tibet, an account of the Japanese Buddhist, Ekai Kawaguchi’s visit to Tibet (1900–1902), had been published by the Theosophical Society, Madras (1909). Ramodar must have read the Hindi translation of Kawaguchi’s account, Tibet mein teen varsh, which was published by Hindi Book Agency, Calcutta (1923). Both David-Neel and Kawaguchi had entered Tibet disguised as monks and perhaps Ramodar gathered a few tips from these books.

Baba Ramodar had always travelled penniless in the expectation that he would find means of sustenance and support wherever he went. But this time things were different; he had just received a hundred rupees from Kashi Vishvavidyalaya as advance royalty for one of his books. His plan was to sneak into Tibet via Nepal without applying for a passport. He would travel incognito until he reached Lhasa, where he would announce his arrival to the Dalai Lama and seek permission from him to stay and study in Tibet. In the Hindi account of his Tibetan travels, Tibet mein savva baras [Fifteen Months in Tibet], published by Sharada Mandir (New Delhi) in 1933, Ramodar describes how he disguised himself as a Buddhist monk. And acquired yet another name: Chhewang from the village of Khunnu in Kinnaur.

On 3rd March 1929, Ramodar started from Raxaul, the last town on the Indian side of the Indo-Nepal border on the high road to Kathmandu. He joined the hordes of pilgrims visiting the Pashupatinath temple on the occasion of Mahashivaratri when Indians could freely travel to Nepal. On reaching Kathmandu, he assumed his Buddhist disguise as Chhewang and sought Tibetan contacts who would be willing to let him join their entourage on their way back home. A Bhutanese lama who headed a monastery in Tibet, impressed by his ardour, agreed to escort him. The journey to Tibet could only start in May. Chhewang used the intervening two months to pick up the Tibetan language and manners so that he could pass off as a Kinnauri monk.

On 14th May, Chhewang began walking with a large group comprising the lama, his disciples and other camp followers. It would be an arduous journey undertaken entirely on foot and involved steep climbs all the way to Lhasa through dense forests, cold deserts, high passes and barren mountains. After two months of incessant walking, Chhewang reached Lhasa on 19th July 1929. He was now back among civilized people. He could take a bath after five months and catch up on back issues of The Statesman. He could send telegrams and letters to his friends and associates. And most importantly, he could now drop the charade of a monk and announce the arrival of Baba Ramodar.

Ramodar addressed the thirteenth Dalai Lama (1876–1933) with a Sanskrit poem of fifteen verses (with a Tibetan translation) presented through a high-ranking official at the Potala palace. After a few weeks, he received permission to commence his course of study. However, lack of money was proving to be a major hurdle. Not only did he have to pay for his food and stay, he also needed money to purchase books and other study material. Just as the harsh Tibetan winter was setting in, Ramodar sent letters to his contacts across India and Lanka seeking funds. When he had given up all hopes of an answer, he heard from Vidyalankara Pirivena, his alma mater in Lanka. They were willing to send funds for his sustenance and purchase of books provided he returned to Lanka forthwith. Ramodar had no option but to accept the offer.

The purchases had to be made within a window of three months so that he could set off from Tibet before the roads closed for winter. He began to purchase books, both printed and handwritten, at a feverish pace. The two main books that Ramodar sought to purchase were printed copies of the canonical Tibetan texts, Kangyur and Tangyur. He describes them as follows:

Students of history know that there was a close relationship between Tibet and north India from the seventh century when Acharya Shantarakshita was in Nalanda to the eleventh century when Acharya Dipankara Shrijnana was in Vikramashila. India is the source of Tibetan religion, script and scripture. Thousands of Indian texts were translated from Sanskrit and other Indian languages into Tibetan. The scale of this translation project can be estimated by the fact that the two compilations of Tibetan translation – Kangyur and Tangyur – extend to over two million stanzas. Kangyur consists of those works which the Tibetan Buddhists associate with the Buddha himself. It can be divided into three parts: Sutra, Vinaya and Tantra. Since the Kangyur is wrapped in hundred bundles, it is considered to have hundred volumes, but in reality, the actual number of books is over seven hundred. Some of the Kangyur texts were first translated into Chinese from which they were translated into Tibetan. The Tangyur not only consists of commentaries on many of the Kangyur texts but also hundreds of books on philosophy, grammar, poetics, astrology, medicine and tantra. This compilation extends to two hundred volumes. The long-lost Sanskrit works of the stars of the Indian philosophical firmament such as Aryadeva, Dignaga, Dharmarakshita, Chandrakirti, Shantarakshita and Kamalashila have been preserved in excellent Tibetan translations.

By the middle of April 1930, Ramodar had succeeded in collecting most of the books including the Kangyur. However, he could not lay his hands on a good copy of the Tangyur. He had no option but to get it printed at the Narthang Monastery Press.

Printing in Tibet

Tibet acquired the technology of printing books from China in the early 1600s. Though typography, that is, printing using moveable type, had long been in use in China and Korea, printing in Tibet was done by xylography. Ramodar describes the technique which he first saw at the Swayambhu Buddhist monastery in Kathmandu:

There was no need for a printing press to print the books. Both sides of a block of wood are carved with two pages of text. The woodblock is placed on the ground; ink is applied on its surface using a piece of cloth; paper is placed on top of it and a roller is manually rolled over the paper on which the text is impressed.

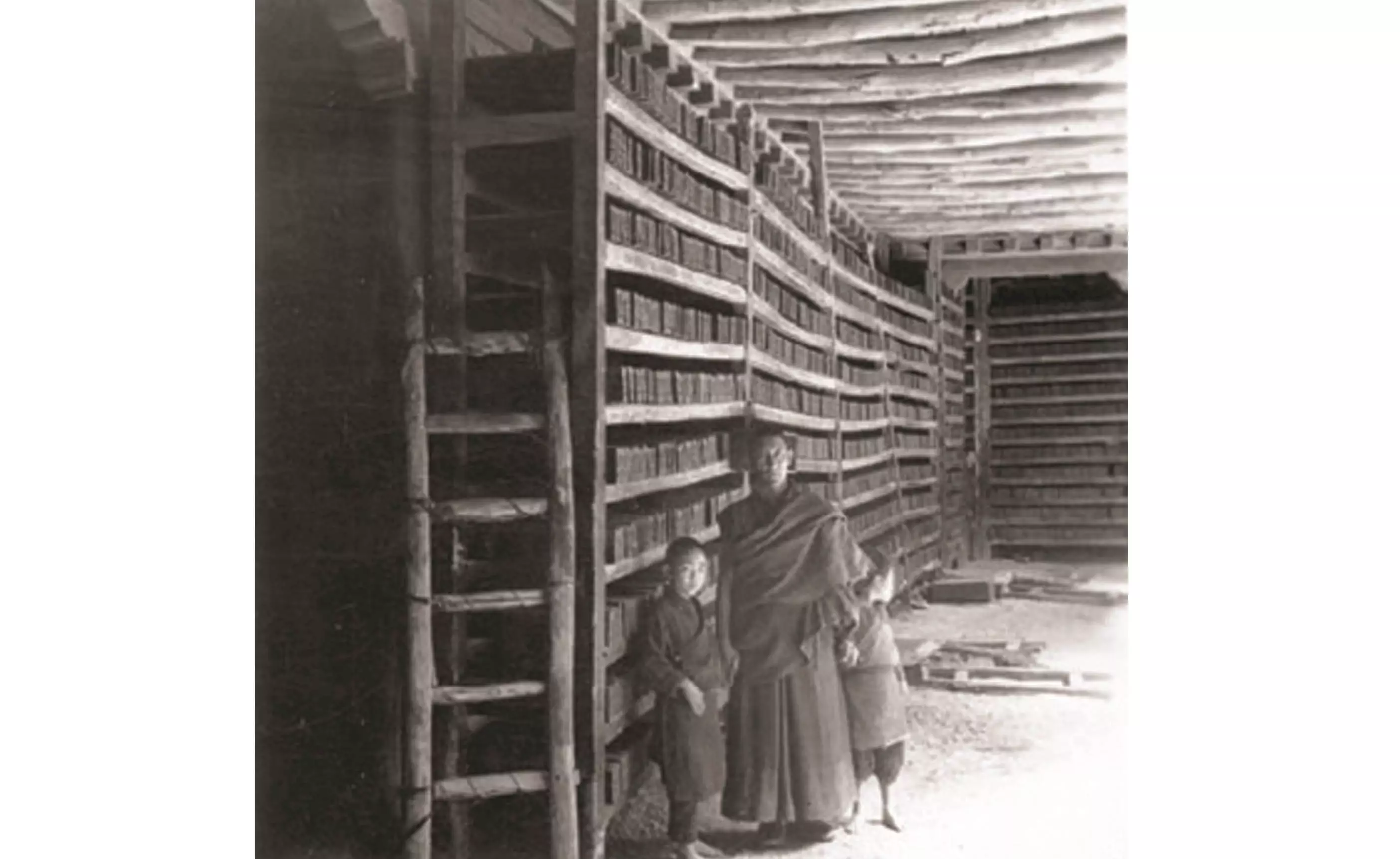

Racks of printing blocks, Narthang Monastery Press, c. 1940s

Needless to say, the quality of printing depending on many variables such as the accuracy of the carved text, the stability of the woodblock on the ground, the evenness with which the ink is applied and the steady pressure with which the paper was pressed to the woodblock. A number of copies of the Kangyur and Tangyur were printed annually from these woodblocks. Ramodar did not want to have anything to do with them:

At Lhasa, I met a trader who told me that he has sent his man to fetch a copy of the printed Kangyur. … The trader is under obligation to annually present a copy or two of the Kangyur to the Mahaguru. He always gets a couple of extra copies printed. Neither does he have to pay any extra charges nor does he incur any transportation costs. I had already seen copies of these ritual offerings at the Potala and I would not accept them even if offered free of cost. They are the worst sort of production. The poorest quality of paper is used and the ink likewise. The printing is so carelessly done that not one line in ten can be read completely.

Ramodar decided to have the Tangyur printed on special paper using good quality ink which he would himself supply. Leaving Lhasa on 19th April, he reached Shigatse on 2nd May where he had to procure the money for the printing.

Once he got the money, Ramodar immediately set to work. After buying the works of the first six Tashi-Lamas at the Tashilhunpo monastery at Shigatse, he purchased paper and ink worth four hundred rupees for printing the Tangyur before going to Narthang.

The Narthang Monastery Press

The Narthang printery traces its history back to the 1730s when Polhanas [the de facto ruler of Tibet at that time] began thinking about a significant project to enhance his religious merits. He decided to commission a new edition of the Tibetan canon. The work of engraving the text of Kangyur on wooden blocks began in late 1730 at a location where wood, never easily available in Tibet, was in ample supply. Skilled artisans were invited from all over Tibet to carve the woodblocks and the entire text was engraved by February 1732. The first printed copy was presented to the Tashi Lama and the woodblocks deposited in the Narthang printery. About ten years later, the engraving of Tangyur was also done. The first copy, which was presented to the Dalai Lama in 1742, is preserved in the Potala library. Arriving at Narthang about two hundred years later, Baba Ramodar describes his first impressions in some detail:

We went to Narthang after a couple of days [of reaching Shigatse]. It is about six to seven miles from Shigatse. Like other old Tibetan monasteries, the complex is set on flat land and is surrounded by walls about twenty feet high and seven to eight feet thick. …Though it is currently under Tashilhunpo (founded 1447), which is a Gelugpa monastery, Narthang is older and was established in 1153 by Lama Tumston. During the Gelugpa reformation, the Narthang monks accepted the changes. There are numerous brass and sandalwood statues dating to the eleventh and twelfth centuries at Narthang. The statues of Indian origin can be identified by the thick brass rings attached to the base; bamboo poles would be inserted through them to transport the statues. There are many old statues in Thubwong and Khamsum. Outside, the four walls of the courtyard have stone facings on which images of the 84 siddhas have been carved.

Alexandra David-Neel, who visited Narthang in the early 1920s, describes the interior of the printing press in her 1931 book, With Mystics And Magicians In Tibet: "I went on to Narthang to visit the largest of the printing establishments in Tibet. The number of engraved wooden plates used for the printing of the various religious books was prodigious. Set up on shelves, in rows, they filled a huge building. The printers, spattered with ink up to their elbows, sat upon the floor as they worked, while in other rooms monks cut the paper according to the size required for each kind of book."

The authorities at Narthang were reluctant to take up the print job even though Ramodar had the permission of the Dalai Lama. They needed some coaxing before they got started:

Since the man who has been designated as the supervisor of the printing press is not very business-minded, the writ of the local magistrate runs here. We finally agreed on a printing fee of 300 srang and were assured that the job would be completed in a week. We returned to Shigatse and sent over the ink and paper the following day. One of the bhikkus in Narthang was the brother of Maniratna Sahu’s Tibetan wife. We were hoping that his presence would ensure a timely completion of the job. But when we sent a man over after six days, we discovered that printing had not yet commenced. On 8th May, we again went to Narthang. Many excuses were proffered but finally the printing commenced. We decided to camp here to oversee the printing.

The print job of the Tangyur was completed on 15th May 1930. Over two thousand rupees had been expended on acquiring copies of Kangyur and Tangyur. Before Baba Ramodar could head back to India, he had to ensure that his purchases were packed in such a manner that they reached Lanka safely:

The pictures and books were first placed in wax-lined envelopes and then packed in wooden boxes. These boxes were wrapped in sackcloth. The uppermost covering was freshly skinned yak leather. These precautions were very useful and saved the books from three spells of heavy rains – first on the mountains near Darjeeling, then on the plains of Bengal, and finally in Lanka.

Epilogue

After a spell of travel within India, Baba Ramodar reached Lanka towards the end of 1930 and was ordained a Buddhist monk. He had to choose yet another name to go with his new avatar. This time he chose Rahul Sankrityayan, a name which stayed with him until his death.

Kedarnath Pandey alias Baba Ramodar alias Khunnu Chhewang alias Rahul Sankrityayan (1893–1963)

Rahul Sankrityayan became a Tibetologist and over the course of the next three decades produced a number of books related to Tibetan religion, history and language. His Tibet travelogue, Tibet mein savva baras, became an instant classic. He undertook three more trips to Tibet and unearthed many priceless treasures which are now housed in the Patna

Museum as are the books he purchased in 1930. The Narthang Monastery Press continued to function until the 1950s but was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution of 1966.

See All

See All