Print History: A visit to a Rangoon print house - Hanthawaddy Press

Burma has a long record of its ancient history and a living tradition where old texts were still relevant. A visit to one of the largest printing presses in Rangoon in 1910 illustrates how these texts were transitioning from manuscript to print.

30 Apr 2022 | By Murali Ranganathan

From 1901, a series of books with the general title, ‘Twentieth Century Impressions of ...’, were issued by the Lloyd’s Greater Britain Publishing Company Ltd. This is the only imprint of the publisher, who was perhaps connected with the insurance firm, Lloyds of London, and had offices in cities all across the southern hemisphere from Buenos Aires in Argentina to Cape Town in South Africa and Perth in Australia. Each book in the series dealt with a particular region or country under colonial rule and was sub-titled ‘Its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources.’

The series was edited by Arnold Wright, a journalist with global experience who had begun his career with the Times of India at Bombay in 1878. The books could best be described as a cross between a government gazetteer and a tourist guidebook; perhaps they were meant to be handbooks for discerning travellers and potential investors. Each volume was sumptuously produced and profusely illustrated with specially commissioned photographs. The series started with a book on Egypt in 1901 and abruptly ended in 1914, the year the First World War started, with one on the West Indies. Besides countries in South America like Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, the series featured Asian colonies such as Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia), British Malaya (now Malaysia), and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). The volume for 1910 dealt with Burma (now Myanmar).

For the Burma volume, the editorial team comprised of Arnold Wright in London and two assistant editors, HA Cartwright and O Breakspear in Rangoon. While the chapter on Burmese history was written by Wright himself, most of the other chapters were written by senior officials – both European and Burmese – in the colonial government. Some chapters were not credited to any specific author and were probably compiled by the assistant editors. One of these anonymously written chapters was on The Press.

The experience of print in the Burmese language is very similar to that in many other Indian languages. It is characterised by the pioneering efforts of Christian missionaries, desultory patronage by indigenous rulers, and a long gradual phase of development of a print culture under British colonial rule. The chapter not only dealt with the contributions of the mission presses but also shone the limelight on a press with a decidedly Burmese character: the Hanthawaddy Press.

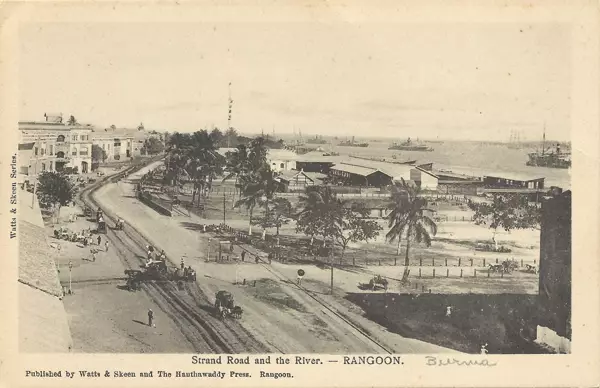

Postcard from Hanthawaddy Press, circa 1895

Hazy origins

The proprietor of the Hanthawaddy Press, Philip H Ripley, believe it or not, was actually more Burmese than his name suggested. Born in 1858, he was the second son of Captain FW Ripley of the British army, who was posted to Kyaukpyu in Arakan after the second Anglo-Burmese War. Very little is known of Ripley’s early life or maternal family and what little is known is confusing; his mother was probably of joint Burmese and Armenian parentage. Like in other parts of Asia, Armenians had a small but significant presence in Burma in the eighteenth century, mainly in the coastal province of Arakan (now Rakhine).

Though they were mainly traders, Armenians were also employed as bureaucrats and high officials in the Konbaung administration. Some of them had married Burmese women and were permanently resident in Burma. In 1868, his father, now Lt-Col Ripley, left Burma in double disgrace; not only had he been severely censured by the British administration for violating rules, he had also taken on a second wife – an Englishwoman – and abandoned his Burmese family.

Philip moved with his family to Mandalay, then the capital of the Kingdom of Burma, where his elder brother, Richard, a mere teenager himself, managed to get a job at the British Residency in Mandalay. King Mindon apparently took a shine to the ‘little redhead’ and treated Philip like a son. Philip was a contemporary and study companion of the Burmese prince, Maung Yay Set, who would later become King Thibaw. The princes, and Philip with them, attended a school conducted by a Christian missionary who had been invited especially for that purpose by King Mindon.

The school was situated just outside the palace walls and the boys gained proficiency in English. Philip seems to have left Mandalay for Rangoon in the mid-1870s, thus escaping the turmoil and bloodshed which preceded the accession of Thibaw to the throne in 1878. Perhaps he had Armenian family connections through his mother in Rangoon which he could rely upon. A colonial city since the 1850s, Rangoon had emerged as the focus of the Armenian community in Burma who built a church there in 1862. Fluent in both Burmese and English, the young Philip could hope for many employment opportunities in a rapidly growing city.

King Mindon, who ascended the Burmese throne in the aftermath of the second Anglo-Burmese War after his half-brother was forced to abdicate, had a progressive outlook and sought to modernise Burma. As part of these efforts, a printing press was set in operation in the imperial palace gardens in 1864. Though mainly used to print religious texts, a newspaper titled Yatanabon Naypyidaw began to be published from this press from 1874. As a young boy, Ripley would certainly have wandered into the press frequently. Perhaps he was even employed there as a printer’s devil.

At Rangoon, he soon found himself drawn into the world of printing and publishing. The Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma notes that:

Mr. Ripley came to Rangoon at the age of seventeen to earn his own living. He first obtained an appointment in the Rangoon and Irrawaddy Valley (State) Railway, and subsequently entered the British Burma Secretariat. While there he assiduously set himself to master the Burmese language under the capable guidance of the late Mr. W. Hadford, Government translator.

After two years’ steady work he was selected for the post of sub-editor of the Educational Gazette, a Government publication, and by the time he was twenty years of age he was acting as Burmese translator to the Government. It was about this time that he became keenly interested in the art of printing, the taste for which was accentuated by his connection with the Government Printing Press in the passing of proofs of Burmese matter for the British Burma Gazette.

Ripley’s connection with publishing and books was further cemented when he was appointed as the manager of the Government Book Depot. He also became a member of Text Book Committee, whose responsibility it was to commission and publish textbooks in Burmese for use in government schools, when it was formed in 1879. The 1870s were a period of rapid growth for print in Burma. Besides the presses owned by the government and missions, Burmese entrepreneurs had also entered the field.

Though the cost of printed books fell because of the competition, this led to serious deterioration in the quality of the printed product. It was around this time that Ripley decided to enter the arena of printing himself. He started a printing press in a by-lane behind the Town Hall. This initiative was described as a “hobby” by the editors of Twentieth Century Impressions, perhaps a nod to the fact that as an employee of the colonial government, Ripley could not have started a commercial venture. The imprints from this press were credited to his brother Richard Ripley. The Hanthawaddy press officially came into existence only in 1883 when Ripley resigned his government employment.

Hanthawaddy Press

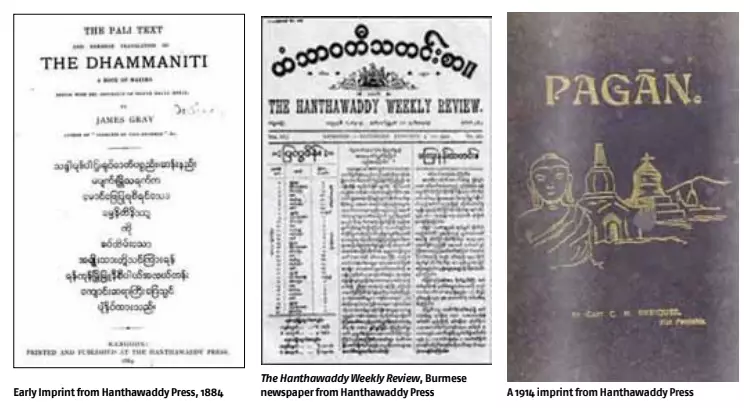

The choice of the name ‘Hanthawaddy’ for the printing press reflected Ripley’s desire to celebrate and promote the ancient literary tradition of Burma. Related to the Sanskrit hamsavati, it was the name of the kingdom which ruled lower Burma until the sixteenth century, and was also the name of the district surrounding Rangoon. Ripley’s primary interest was in publishing carefully edited Buddhist texts but he also ensured the commercial viability of the press by printing textbooks, reports, and mundane job orders. The Hanthawaddy Press began publication in 1884. Perhaps one of the first imprints from the press was The Dhammaniti: A Book of Maxims which contained the original Pali text and a Burmese translation.

The upshot of the third Anglo-Burmese War of 1885 was the deposition of King Thibaw and the annexation of Upper Burma by the British. Burma was now a province of British India. The printing press established by King Mindon in the 1860s had continued to function all these years, but the colonial rulers shut it down and auctioned its assets soon after. Ripley also managed to acquire a printing press from the old royal press for the Hanthawaddy Press. By the 1890s, after ten years of operation, the Hanthawaddy Press seemed to have achieved a pre-eminent position in the printing industry in Burma.

The purchase of Burmese type had always been a hurdle for presses owned by Burmese entrepreneurs as they had to rely on the American Mission Press in Rangoon which had the only type foundry in Burma. They could also import the type from Calcutta or London but that would have been an expensive proposition. Ripley decided to set up a type foundry for his own requirements and also sell type to other Burmese printers. He made a year-long trip in 1895–96 to London to learn more about the business and purchase a type foundry.

The trade magazine, British Printer (May-June 1895), was delighted to make his acquaintance: “Mr. Ripley [is] a genuine enthusiast in all that concerns printing. His enthusiasm for good work has received many cruel blows by the difficulties he has had to meet in the pursuit of his craft but he has risen supreme to all this and the printing art has evidently no more devoted follower than our friend from Rangoon.” Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma describes Ripley’s progress thereafter:

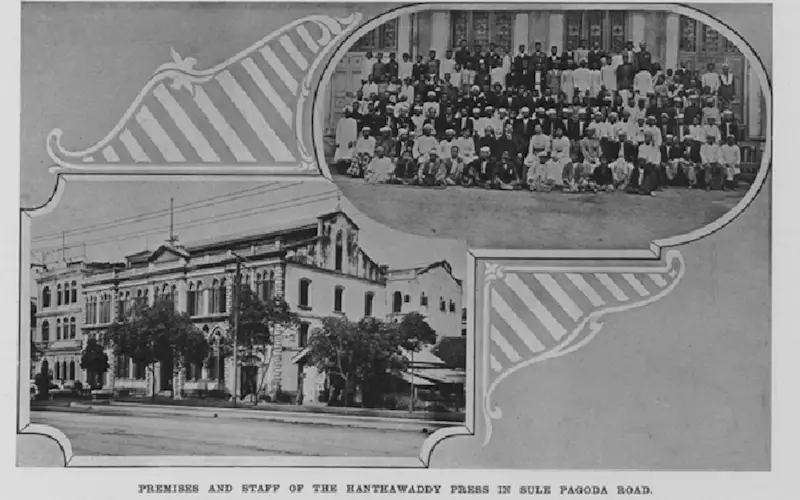

On his return to Rangoon in 1897, he brought with him complete plant for a type foundry, which he set up in the present commodious premises known as the Hanthawaddy Printing Works, at 46, Sule Pagoda Road. The building, which is four storeys in height, has a floor space of 6,000 square feet. In the new home of the Hanthawaddy Press the printing of Burmese literature continues to be the main work undertaken, special attention being directed to the publication of Burmese classics, which are found inscribed upon palm leaves in the various monasteries throughout the country.

The Press undertakes not only printing in English, Burmese, and Tamil, type-casting, and stereotyping, but also bookbinding, rubber-stamp making, engraving, and the making of photo-process blocks. During recent years the business has grown steadily, and at the time of writing new works are in course of erection in the suburbs of Rangoon, and a branch is about to be opened at Mandalay. Among the periodicals and newspapers published by the Press are the Rangoon Advertiser, an English paper, and The Hanthawaddy Weekly Review, which is printed in Burmese, and contains general news, translations of Reuter’s telegrams, and commercial information calculated to be of interest to the Burmese. The firm employs four Burmese editors, the chief of whom is an ex-official of the Court of the late King of Burma, and over 180 hands are engaged in the works.

The largest book in the world

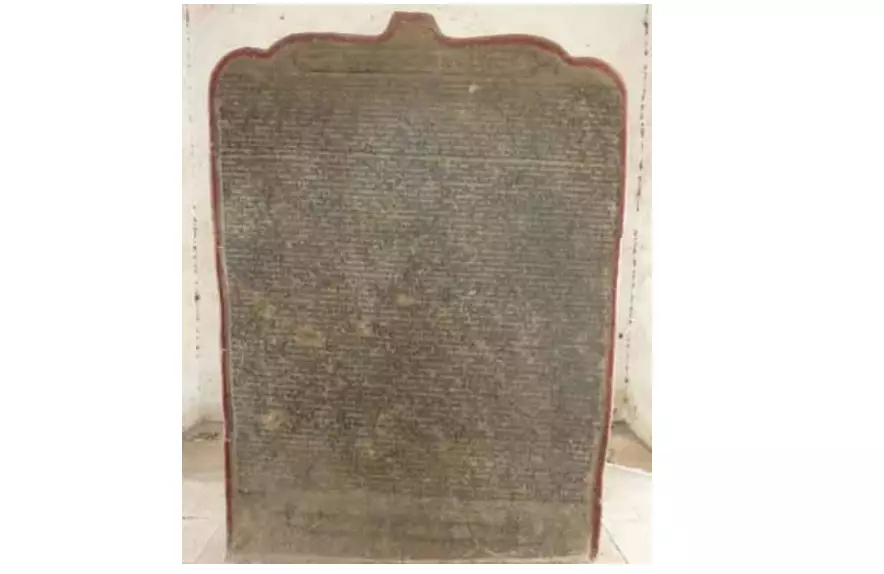

As a nation which claims an uninterrupted Buddhist tradition since the times of the Buddha, religious texts play an important role in Burmese culture. In the era before printing, producing a copy of the text could be a means of gaining religious merit. However, the authenticity of the text was of paramount importance. King Mindon, who had established a new capital at Mandalay, constructed the Kuthodaw pagoda to consecrate the site. He also took up the expensive, arduous, and therefore, highly meritorious project of carving the entire text of the Tripitaka, the Buddhist canon in the Pali language.

A page from the largest book in the world, Tipitaka at Kuthodaw Pagoda (Image credit: photodhrama.net)

The text was engraved in Burmese script and inscribed in gold ink on both sides of 730 marble tablets, amounting to 1460 pages. Each tablet, a little over five feet tall and 3.5 feet wide and 5 inches thick, was housed in a mini-pagoda – chedi – of its own. The project, commissioned in 1860, took eight years to complete, and was inaugurated just when the Ripley family moved to Mandalay. The young Philip would have wandered among the chedis with his playmates. Many years later, Ripley, who had always been keen on discovering authoritative texts, conceived the idea of printing the Tripitaka based on the text of the largest book in the world. The Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma notes that:

As a young man Mr. Ripley cherished an ambition to make these writings known, and, in spite of discouragement, even from the Buddhist priesthood, he resolutely set about the task. The work took many years to accomplish. The complete Tripitaka comprises thirty-eight printed volumes. The proofs of this work had to be sent for revision to Mandalay, where the whole of these scriptures, engraved on marble slabs, are placed round a pagoda at the foot of Mandalay Hill. The demand for the volumes is steadily increasing.

Life thereafter

By 1910, Ripley had been joined by his two sons at the Hanthawaddy Press. Both of them had been trained at the best printing schools in England and helped modernise the press, especially in the area of printing illustrations. When Ripley died at the age of eighty in 1939, the Hanthawaddy Press was at the height of its career. Besides the magnum opus Tripitaka, Ripley had systematically printed numerous other texts related to the Theravada tradition of Buddhism over five decades and more of printing. Burma witnessed many upheavals in the next three decades but the Hanthawaddy Press seems to have soldiered on before it disappeared in the 1970s.

The premises at Sule Pagoda Road of Hanthawaddy Press from Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma: Its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources, 1910

References

- Arnold Wright (ed.) Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma: Its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources. London, 1910.

- Gracie Lee. Early Printing in Myanmar and Thailand. Biblioasia (Jul-Sep 2020): 46–49.

- LE Bagshawe. A Literature of School Books: A Study of the Burmese books approved for use in schools by the Education Department in 1885, and of their place in the developing Educational System in British Burma. Master’s thesis, University of London, 1976.

- Yan Naing Lin. Mandalay and the Printing Industry. Mandalay University Research Journal, Vol. 7 (2016).

See All

See All