Print History: Animesh Mohapatra - Excavating Odia Print Culture

While teaching English at a Delhi University college, Animesh Mohapatra has been excavting and illuminating various facets of Odia print history and culture. In this interview, he outlines his research interests which extends from the earliest Odia texts to contemporary discourses

30 Sep 2023 | By Murali Ranganathan

What was your earliest interaction with print?

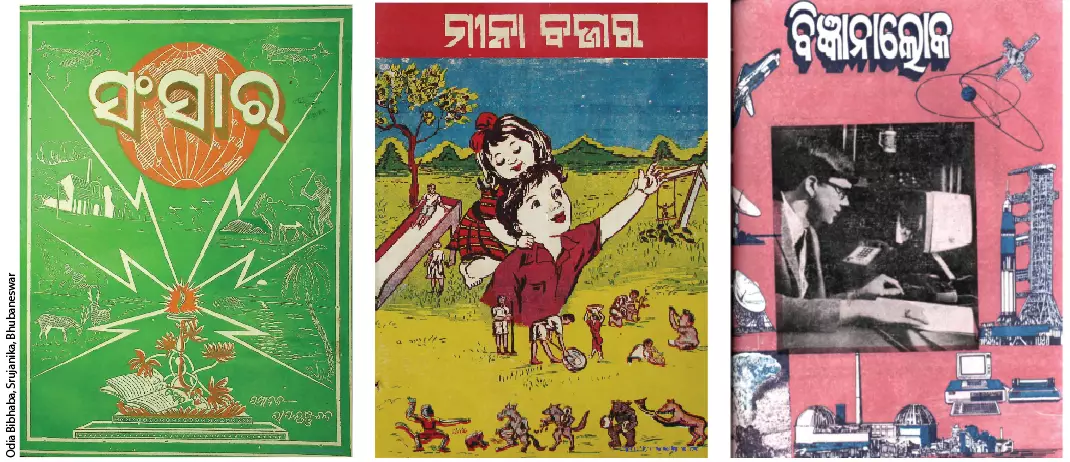

The first ten years of my life were spent in a picturesque village in the coastal district of Kendrapada in Odisha. What I remember with particular fondness is the number of children’s magazines my uncle brought home for me and my siblings. Every Saturday, the sound of his cycle bell would fill us with eager anticipation. We would devour a dozen magazines every month but still clamour for more. These Odia magazines were indicative of a thriving publishing industry in Odisha in the 1980s and 90s. While most contained stories and poems, a few magazines tried to popularise science and maths among children. I can instantly recall names such as Meena Bazar, Sansara, Biluanana, Sunapila, Baramaja, Kandhei, and Sishulekha. And, of course, there was Jahnamamu, the Odia equivalent of Chandamama. These would also feature sections on general knowledge, puzzles, riddles and crosswords. I would turn to science-centric magazines such Bigyanaloka, Bigyan Prabha and Bigyan Tarang only when I exhausted the magazines that carried stories. Biographical sketches of scientists and inventors such as Newton, Franklin, Edison and Bose particularly appealed to me. With the increasing availability of other sources of entertainment, the number of children’s magazines dwindled.

What about English language materials? Where they easily available in Odisha at that time?

The only reading materials in English I was exposed to included a handful of textbooks and a newspaper. Everything else I read was written in Odia. Magazines targeting teenage readers were virtually non-existent. It’s only when I joined Christ College, Cuttack as a student of English literature that I gradually resumed reading for pleasure. And this time all the books I read were written in English. Rather than rely on college libraries, I turned to the multiple second-hand bookshops, which sold used books at prices I could afford. These shops would give us access to titles published in Oxford World’s Classics and Penguin Classics for as little as forty rupees. I remember getting copies of One Hundred Years of Solitude and Dubliners from these shops. I did not return to reading Odia books and periodicals until I started formulating my PhD proposal at the University of Delhi in 2008. And then I began to explore the rich resources of Odia literature and culture, and sought to reinterpret them through fresh perspectives.

How did you engage with Odia print history for your doctoral research?

In my doctoral dissertation, I tried to examine how the local and the national were formulated in the Odia public sphere in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the 1860s, with the setting up of the first printing press by Odias and the launch of the first newspaper Utkal Dipika, there emerged an increased consciousness among people of the region that they were speakers of the Odia language as opposed to people who spoke Bangla, Telugu and Hindi. Since Odia-speaking areas lay scattered in different presidencies and provinces, from time to time there would be suggestions to replace the use of Odia in schools and offices by other languages on grounds of administrative convenience. Agitations against such moves consolidated linguistic identity among the people which led in 1936 to the creation of Odisha, the first linguistically carved province in India. The demands of the Odia-speaking people for a united province was initially seen as running counter to pan-Indian nationalist aspirations. My dissertation throws light on the complex negotiations between local language-based aspirations and the pan-Indian nationalist movement. It was the wider access to printed texts, and not the growing preoccupation with the place of Lord Jagannath in Odia culture, which played a more crucial role in crystallizing a sense of Odia identity.

Cover pages of children’s magazines: Sansara (1955), Meena Bazar (1962) and Bigyanaloka (1990)

What were the tensions which emerged as Odisha made the slow transition from a largely manuscript culture to one where print began to dominate?

In the course of collecting material for my research, I increasingly became aware of the pivotal role that print culture played in shaping this public sphere. I was fascinated by the ways in which the transition from palm-leaf pothis to printed books introduced new reading practices, brought literature to the marketplace, redefined the very idea of literature and consolidated a sense of Odia identity. The shifts within the domain of literature were not always seamless and led to a bitter literary controversy between the defenders of the “ancients” and the advocates of the “moderns” in the 1890s. These battles were often fought on the pages of literary magazines. While Indradhanu (Rainbow) echoed the views of the defenders of the ancients, the promoters of the moderns voiced their thoughts in Bijuli (Lightning). As an outcome of this battle, new modes of evaluating literature emerged and texts composed in the pre-print era underwent revaluation. For example, in the early twentieth century, the works of the fifteenth-century Odia poet Sarala Das were read afresh and he soon came to be regarded as the adikavi or first poet of Odisha.

Can you describe how Cuttack emerged as a hub for Odia printing and publishing?

Printing of Odia books began in the first decade of the nineteenth century under the auspices of the Serampre Mission Press. The first printing press in Odisha was established at Cuttack in 1837 by Christian missionaries. The Cuttack Printing Company was formed in 1865 by a group of Odia entrepreneurs. The devastating famine of 1866 prompted the need for articulating popular grievances and the first newspaper Utkal Dipika was brought into being to address this need. Its first few issues were lithographed but soon it was printed from type for which the fonts had been specially commissioned. Although printing presses functioned in different parts of Odia-speaking regions such as the city of Balasore and the feudatory states of Mayurbhanj and Bamanda, Cuttack emerged as the hub of print culture in Odisha in the nineteenth century and continued to dominate the scene till the end of the twentieth. A whole print neighbourhood, comprising the three streets, Balu Bazar, Banka Bazar and Binod Bihari, is devoted to publishing and selling books and continues to remain vibrant even today.

How has your interest in print intersected with your research in other areas of Odia culture?

Any scholar working on society and culture in nineteenth-century India cannot afford to overlook the emergence and impact of print. While researching jananas, devotional songs in Odia addressed to Lord Jagannath, I had initially planned to focus on the cassette industry. However, I soon realized that the impact of print on devotional songs could not be ignored altogether. The journey of this genre through several discrete but overlapping forms of circulation – performances, palm-leaf manuscripts, printed songbooks and audio recordings – is very interesting. After the introduction and consolidation of print, the genre lost its former canonical status and began to be relegated to the domain of the non-literary. With recording technology gaining widespread popularity, the genre got reinvented and carved a separate space for itself in the larger cultural domain. In the late nineteenth century, after the consolidation of print in Odisha, secular forms of writing acquired greater prominence in the public sphere, a perceivable separation among intellectuals and masses took place and devotional songs were moved to the domain of popular literature.

What have you published?

Most of my works are collaborative and touch upon aspects of book history and print culture. Translation remains a crucial element in the projects I have undertaken. My publications include several translations and I generally focus on translating non-fiction/knowledge texts. In my publications, I have made extensive use of texts translated from Odia.

A book chapter which I wrote for The Bloomsbury Handbook to the Medical-environmental Humanities (2022), analysed Odia texts on health written in the first half of the twentieth century and found how indigenous knowledge systems deftly negotiated with Western understanding of the human body. My research essay “Land of Wonders: Kolkata as Setting in Odia Lietrature” was published in the volume Celebrating the City: Kolkata in Indian Lietrature (Sahitya Akademi, 2021). In the essay, I discussed how, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, several factors drew Odias irresistibly to the imperial metropolis which is presented as a place that is fast-paced, liberal, non-hierarchical, and a site of large-scale violence in Odia literary texts.

.png)

Swargiya Jatrira Brittanta (The Pilgrim’s Progress), Calcutta, 1838

With Jatindra Kumar Nayak, I co-edited a volume comprising twenty-five critical essays in English translation which was published with the title Critical Discourse in Odia (Routledge, 2022). We worked with nearly two dozen translators to identify and translate important critical essays which were published in Odia between 1897 and 2016. In the introduction, we offer a brief account of the emergence and development of a critical tradition in Odia, the tradition of reflecting on cultural objects and phenomena. Several essays in the volume deal with various aspects of print history and culture. One essay focuses on the convention followed in colophons of palm-leaf manuscripts. The system of patronage and attribution of authorship constitute the subject matter of another essay. Other subjects include the changing commercial prospects of Odia literature and the literary controversy that erupted in the 1890s between two periodicals over the relevance of precolonial Odia literature. Together, these twenty-five essays essays offer an overview of the history of Odia literature and criticism.

I also edited, with Sumanyu Satpathy, a volume of essays (in English translation) by Natabara Samantaray, who is arguably the most outstanding critic of modern Odia literature (Sahitya Akademi, 2017). Starting from the early 1950s, he presciently foregrounded the significance of print in the development of modern Odia literature. Some of the essays featured in the volume though offer fresh insights on authors and texts from the precolonial period. A chapter in the book makes a detailed analysis of the role textbooks played in shaping literary taste in the late nineteenth century.

I have co-compiled an annotated bibliography on the temple town of Puri which will be included in Oxford Bibliographies in Hinduism (forthcoming 2023). In spite of the deluge of material available on the Internet, bibliographies continue to be important as researchers would still look for a reliable list of texts published on a particular subject.

How has Odia print history been documented?

In Odisha, only a handful of books have been written directly on the history of print. Pathani Patnaik’s Odia Prakashanara Itihasa (2013) and Manjushri Dhall’s History of the Printing Press in Orissa, 1837-1947 (2013) immediately come to one’s mind. Graham Shaw’s “The Cuttack Mission Press and Early Oriya Printing” (1977) remains an authoritative work on the history of early printing in Odisha. Jatindra Kumar Nayak’s research articles “Sacred Time, Secular Space: The Printed Oriya Almanac” (2009) and “The Encyclopaedist as a Cold Warrior: A Perspective on Odia Gyana Kosha or Encyclopedia Orissana” (2020) are informed by print history.

How do you see the study of book/print history evolving over the next few years, especially in the Indian context?

The triad of authors who write books, readers/critics who respond to and evaluate the publications, and the publisher/printers who brings them to the public realm remain central to the process of dissemination of literature and knowledge. However, in the Indian academic sphere, focus lies squarely on authors and readers/critics, and often excludes the publisher. The neglect of the publishers’ role in shaping the conditions under which knowledge is produced and disseminated prevents us from acquiring a fuller understanding of culture and society. The relationship between the publisher and the author, direct and indirect forms of censorship, compulsions of the marketplace, varied networks for distribution of books, creation of reading communities through periodicals, role of illustrators, advertisements, book fairs, awards and honours, and so much more are yet to receive the scholarly attention they deserve.

.png)

The widespread availability of digital texts on the internet has changed the mechanics of research. What has been the Odia experience?

When I started my research on nineteenth-century Odisha in 2008, I had to make several trips to the Odisha State Archives and several libraries to access printed material from the period. It would take a lot of time and effort to go through the brittle pages of the periodicals. However, the situation changed quickly when Odia Bibhaba, a website under the auspices of Srujanika, started hosting Odia books on a very large scale. The organization has digitized more than ten thousand books, most Odia newspapers and periodicals from the pre-Independence period, and a number of dictionaries. Such a repository has made the job of researchers easy in some sense but there is also the problem of plenty. Since the archive is, literally speaking, at our fingertips, the nature of work expected of researchers has also changed. It’s no longer enough to recover important texts or documents that had sunk into oblivion but such texts need to be placed in a larger narrative frame. The Odisha State Museum has made available digitized versions of palm-leaf pothis to the public.

What are your current research and translation projects?

I am working on an article on the making of modern Odisha where I emphasise the role of print culture in shaping Odia identity. I also plan to translate Hajila Dinara Smruti (Memories of a Lost Time), the autobiography of Krushnachandra Kar, the most celebrated proof-reader from Odisha. The book gives a vivid and detailed account of the printing and publishing industry in Cuttack in the 1920s and after.

I am also co-translating Madala Panji, a chronicle of the Jagannath Temple from the pre-print era. The text is often used by historians as a source book and furnishes one of the few instances of extensive use of Odia prose before Odia intelligentsia and European missionaries started popularizing prose as a medium of expression in the nineteenth century. My editing projects included the writings of eminent Odia author and researcher, J P Das and Basudev Sunani, a prominent dalit voice from Odisha, in English translation.

See All

See All