Print History: Howard Iron Works- Reinventing Print

The amazing journey of a Canadian print company from refurbishing printing presses to establishing a world-class printing museum

18 Aug 2021 | By Murali Ranganathan

A vibrant pre-owned printing equipment ecosystem has been the mainstay of the printing industry in many countries where printing economies do not justify higher investments. As businesses at the upper end of the value chain trade in old machines for new, original equipment manufacturers have recycled these older machines to other buyers. The ecosystem consists of vibrant online marketplaces like Press Xchange, large dealers such as J J Bender (US) and Camporese (Italy), and numerous other intermediaries like brokers and refurbishing experts. It is a global industry worth billions of dollars and used machines from Europe, North America and Japan can find new owners in Africa, South America and Asia. Geared towards moving equipment from one user to another, possibly across continents, in the shortest time possible, it would be unreasonable to expect this part of the print world to pause and look back at printing in the days gone by.

But stranger things are known to happen.

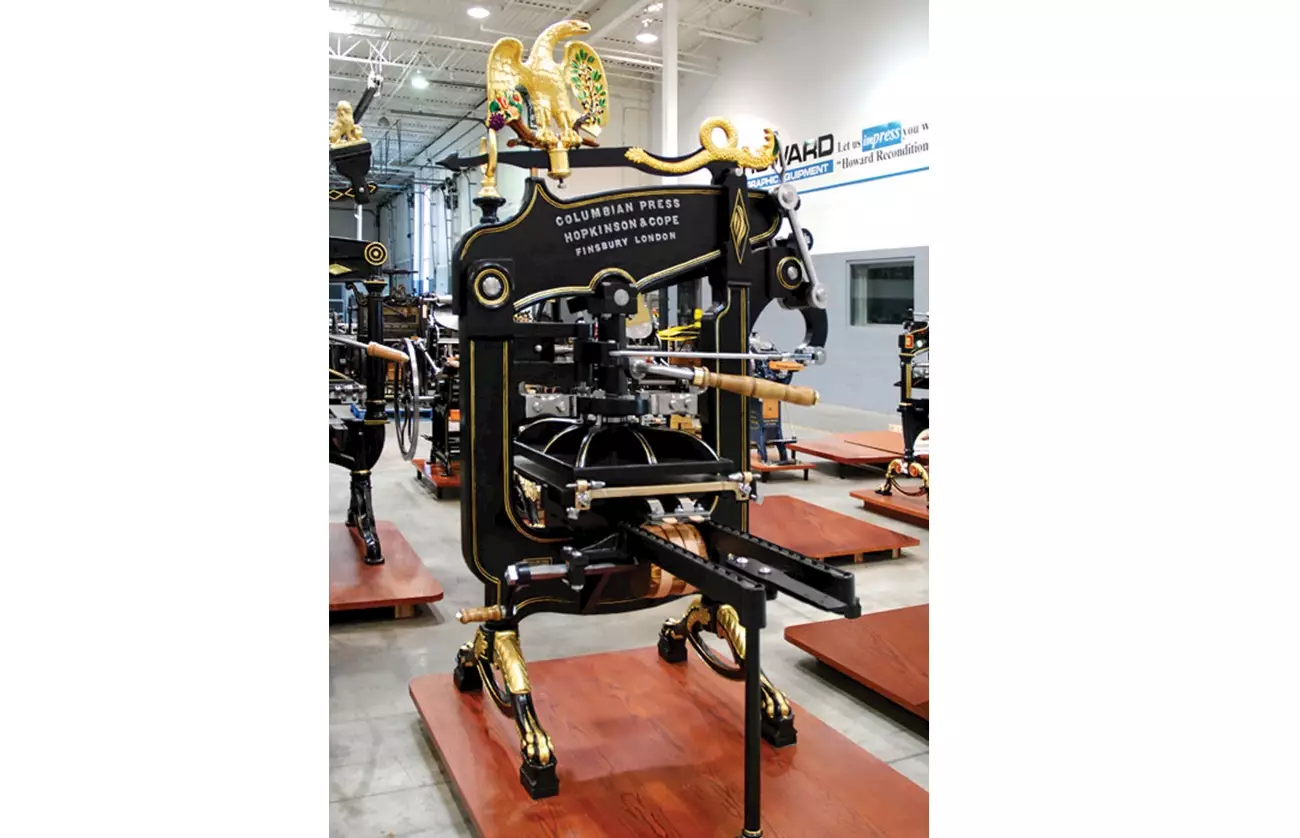

Columbian Hand Iron Press by V & J Figgins, 1886

A seed of a museum

The Canadian company, Howard Graphic Equipment, was founded in 1967 as a used equipment selling business and soon focused on selling commercial printing equipment. It would buy old equipment, overhaul and restore them, and then sell them to customers around the globe. Working with equipment made by leading brands such as Komori, Heidelberg and Roland and old workhorses like Planeta, they would travel to customer location to install refurbished machines and ensure that they were working as per specification. At last count, printing machines refurbished and sold by Howard have been installed in seventy-five countries.

Claybourn Ink Conditioner, 1920s

As a teenager in the 1970s, Nick Howard would pop into his father’s huge workshop in Mississauga, Ontario every weekend to help out. Nick started out by cleaning printing equipment and putting machines together. By the time he started working full-time with Howard Graphic Equipment in 1976, Nick Howard was looking forward to a lifetime in the printing industry.

Along with his wife Liana, who soon joined the business, Nick would travel around the world installing and testing their printing equipment. Somewhere along this journey, the Howards started buying old printing presses which were no longer relevant in the commercial sense and set about restoring them. And in a few decades, the Howards had put together the largest collection of restored presses in the world.

In the early 2010s, the Howards, now at the cusp of retirement, were wondering how to protect their legacy. As Nick Howard recalled in an interview:

First of all, we wanted to make sure we saved a lot of the equipment, and unless we had a place for it, and we restored it, lot of the equipment would just go to scrap. Secondly, because we have spent our whole life in the industry, we wanted to do something else for other people, and the only way we thought to do that, remaining within the industry that we knew, was to set up a museum.

And thus was born Howard Iron Works.

The Collection

The Howard Iron Works Printing Museum moved into custom-built premises in Oakville near Toronto, the largest city in Canada in 2016. The museum is focussed on printing equipment from the 1830s to the 1950s, a period that, according to Howard, “was an exciting time for not only worldwide technology, but also improvements to the printing press.”

The generously proportioned rooms of the museum house row upon row of gleaming printing machines, many of them in perfect working order. All kinds of printing equipment and all major manufacturers are represented. From iron presses built in the first half of the nineteenth century to cylinder and platen presses from the twentieth century. Perhaps the oldest machine in the collection is an 1831 Albion press manufactured in London. It has the world’s largest collection of Columbian presses located at one site; these elaborately decorated presses with their distinctive eagle counterweights dominate the display. Besides it has a few

lithographic presses and a collection of old lithographic stones.

The museum has hundreds of unique items to explore. The original lock-up of the first page of the New York Times announcing the first human landing on the moon on 20 July 1969 is on display. Or one could spot a small tabletop machine used to print on pencils. It also has a Claybourn Ink Conditioner from the 1920s which was used to blend inks by printers. The museum’s library houses an impressive collection of ephemera, print journals and machinery manuals.

Golding Pearl No. 1 Platen Press, 1896

A Print Wonderland

According to print industry veteran, Frank Romano, the Howard Iron Works is “one of the most unique printing museums in the world.” Another visitor, referencing Lewis Carroll’s classic Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, rhapsodises: “The place is Wonderland. You look around and realize that you are, already, down the rabbit hole.”

Over the years, the Howard Iron Works has developed restoration expertise which is now scarcely available elsewhere in the world. Each machine they encounter is unique; it is perhaps the last surviving specimen of its kind or one of the very few around the world. The engineering skills involved in restoring these machines, many from the nineteenth century, is not easily replicable. Building up an inventory of parts that can be cannibalized for restoration is a decades-long process.

Nick and Liana Howard

Howard Iron Works also has an excellent digital printing museum on the internet. Its website, which has been created in-house, provides any armchair visitor with a great museum experience. The detailed text complements the excellent illustrations of machines. The restoration process is also well documented. The website also showcases the print philosophy, encapsulated in this statement by Nick Howard, which has guided the Howards in their journey.

The most powerful machine ever developed by man was not the nuclear reactor nor the computer. It was the printing press without which neither would have seen the light of day.

The museum is not just about printing. Any revenues generated through ticket sales, venue hire, machine rental, and gift-shop sales are channelized to other philanthropic activities. The Howards have generously supported initiatives to increase awareness about breast cancer. To underline their support, one of their Columbian presses has been painted an eye-catching pink and displayed at events. Well integrated with local cultural and art circles, the museum attracts about a thousand visitors every year. From 2018, it has been organizing an annual Print Expo & Book Fair which celebrates the art and technology behind printing with participation from the entire spectrum of print.

A parting word of advice from Nick Howard to any new printing museum: “Realize that whatever artifacts and machines you collect will be superseded by better and more unique ones later. So don’t try and take everything you find.”

A textbook case of restoration

Linotype Model 31

- Manufactured: 1953

- Acquisition cost: US$ 500

- Transportation cost: US$ 1,500

- Restoration cost: In-house

Called the ‘eighth wonder of the world’ by Thomas Edison, the Linotype changed the world of printing and typesetting immediately after it was first designed in the 1880s by Ottmar Mergenthaler. The machine completely revolutionised the production of newspapers and magazines and soon became the mainstay of all major printers. Competitors such as Monotype, Intertype, and Bhisotype soon emerged but Linotype carved a niche for itself. It continued to be produced into the 1970s.

The Howard Iron Works had acquired a 1939 Mergenthaler Linotype Model 14 Linecaster from a printing press in Utah but wanted a newer model which it could maintain in running condition. They managed to acquire a 1953 model at the closure sale of a New York printer in 2017. Though the machine seemed to be in a good condition, it was not operational.

After transporting it to their premises at Oakville, the machine was first given a thorough cleaning. Through their contacts with the artisanal publishing world in Canada, they were able to identify a person with experience of hot-metal composing on an Intertype machine to have a look at the machince. He could soon figure out that the machine was missing a few parts. Luckily, the machine had been sold with a large wooden crate marked ‘Linotype Parts’. It also contained the original manual for the machine and numerous parts, all labelled for easy identification. It was then a matter of putting things together which the experienced team at Howard Iron Works soon managed. The rubber rolls which underlay the keyboard were then rebuilt. Once the electrical connections were cleaned, the machine was ready to cast.

The machine is on display at Howard Iron Works and can be set in operation at an hour’s notice. It is used for demonstrations during major events at the museum.

See All

See All