Trade publishing is like Bollywood

With clear divide between commercial and literary.

If you are connected to trade publishing in some capacity, chances are you have heard of Kanishka Gupta. He is the founder of South Asia’s largest agency and literary consultancy, Writer’s Side, and the person who popularised literary ‘agenting’ in India. Gupta talks to Dibyajyoti Sarma about the state of Indian trade publishing in transition.

14 Sep 2016 | By Dibyajyoti Sarma

Dibyajyoti Sarma (DS): In the last few years, India has witnessed a publishing renaissance, especially in English. Once, a sale of 3,000 copies was considered a bestseller. Now, we have authors like Chetan Bhagat and Amish who have sold more than a lakh copies. There are many new publishers in the market. How do you see the current and future book markets in India?

Kanishka Gupta (KG): It is true that there has been a spurt in the number of publishing houses and books being published, but the hard fact is that even today, a majority of the books just about manage to sell out their first print run. Most translated fiction and some literary fiction and non-fiction continue to have small print runs of 1,500 to 2,000 copies. Even the commercial fiction genre pioneered and popularised by Chetan Bhagat has very few new success stories. You have the same handful of authors who keep churning out books every year and hogging the Amazon and Nielsen bestseller lists. The current scene in publishing is, in fact, no different from Bollywood with a clear divide between commercial/masala and literary/art house. In the coming years, I see midlist fiction completely dying out, greater emphasis on non-fiction, and rise of specialist or niche publishers catering to a loyal readership.

DS: Post-Midnight’s Children, Indian Writing in English (IWE) was dominated by literary fiction, barring a Shobhaa De here and there. Now, we have a legitimate pulp genre. Yet, we seem to be uncomfortable about popular writing, as the backlash against Chetan Bhagat suggests. What are your views about the future of pulp writing in India?

KG: I think this is because most pulp writing coming out of India is generally bad and clichéd. I like to call such books ‘packaged bestsellers’ with everything from the writing, storyline, the title and even the cover seeming predictable and formulaic. There are exceptions like Anuja Chauhan, but they are very few and far between.

In the case of Chetan Bhagat, the backlash is not as much against his novels as it against his undeservingly appropriating the literary space and passing himself off as a social commentator and saviour for the Generation Next. Publishers have long resigned themselves to this phenomenon and are actively encouraging and developing such writing. However, there are those like Hachette, Pan Macmillan, Speaking Tiger and so on, who will never publish a vacuous, badly written commercial fiction even it entails a substantial loss of revenue.

DS: In the recent years, everyone seems to be writing novels. This, of course, is good for the industry, especially the printing industry. But what about readership? Are there enough readers in English?

KG: There is a joke going around in the publishing circles that these days everyone is writing a book and we have more writers than readers. Of course, there are readers but I still feel that IWE is relatively new and even Indian readers prefer to read Western authors over Indian ones. While commercial fiction has burst onto the scene turning some writers into household names, there are several genres like young adult, horror, science fiction, fantasy, speculative and so on that don’t have any home-grown stars. I think this imbalance will be rectified in time.

DS: Unlike the West, traditional wisdom suggests that one cannot make a living as a writer in India. As a literary agent, what do you think about the reality? Is the situation changing?

KG: I don’t know why there is this perception that a book deal in UK or the US means a lifetime of riches. The truth is that not every author publishing overseas gets the coveted million dollar advance. In fact, in many cases the advances are as low as a few thousand dollars and sometimes even under a thousand dollars. One of my own authors, who published with a famed editor of several award winning books, including the Man Booker Prize, was the recipient of such an advance. Not only in India but globally, there are very few ‘full-time writers’. It’s an irresistible, tempting but quixotic term. In fact, most famous and award winning writers, Indian or otherwise, have full-time teaching or other jobs. Ravinder Singh runs a publishing house and Durjoy Datta writes for television. With advances for first time writers ranging from Rs 50,000 to 200,000 payable in two or three instalments and a good, fully realised, full length book taking at least one year of the authors’ time, not only can writing not be a full time profession for 99% of the writers in India, but authors cannot even afford to take long breaks from their full time jobs to work solely on their books.

DS: As a literary agent, you are privy to writer’s expectations more than anyone else. What do writers want?

KG: It varies from writer to writer. Some writers are just happy to get a foot in the door and are not particular about advances and so on, whereas there are others who will not sign away rights to their book below a certain advance royalty even if the publisher is big and reputed. There are many who have a particular preference in terms of an editor and a publishing brand and would like to go with them even if a rival is offering better terms. While traditionally an agent’s job is to find the best possible deal for their author, I believe finding an editor who is enthusiastic and shares the author’s vision is more important than plain monetary considerations. This is very important because even for one project, an author-editor relationship can last for a couple of years if not more.

DS: Of course, the ultimate goal is to be a bestseller. Authors want a bestseller. Publishers want a bestseller. But not everybody can be a bestseller, can they?

KG: I don’t think anyone has been able to crack the formula for writing a bestseller although I think it’s a combination of X-factors such as luck, right timing, market requirement, accessibility and ability to establish a mass connect. My ex-boss Namita Gokhale once said, ‘Every book has a life, a kundali, of its own, which has very little to do with purely literary merit.’ I totally agree with her.

DS: Now that we have established that eBooks are not going to replace printed books and printed books will continue to have major market share, do you think there will be a change in how printed books are produced?

KG: I think all reputed and mainstream publishers are capable of producing handsome books and they are doing just that. Although sometimes quality suffers because of margins and low price points.

DS: There are more books in the market than one can possibly read. The publishers seem to be doing well. Yet, when we talk to them, all say that the market is bad.

KG: I have been hearing about the recession in publishing since I started my career. I think publishers say this primarily because of low margins and how publishing as an industry stacks up to other industries. I daresay that some big individual businesses alone would be having a higher turnover than the entire publishing industry. A 20-something fresher from an IIT or an IIM probably gets a higher salary than a veteran editor with decades of experience. This year has been very good for publishers across the board and new entrants like Juggernaut are stirring things up.

DS: Pricing of a book seems to be concern. Readers seem unwilling to spend more on a book, yet due to rising printing costs, a publisher cannot sell a book beyond a certain price. Hence, online retail sites seem to be selling more books than traditional bookstores.

KG: India is a very price-sensitive market. Unfortunately, this has started impacting publishing and editorial decisions. Many publishers routinely turn down coffee table books, graphic novels, illustration-heavy books (recipe or children’s picture books, for instance) or even books that exceed a certain word count because the pricing would make them prohibitive for most buyers. At times, suggestions for drastically shortening a book seem to go against logic and the sanctity of the narrative. Price-sensitivity is one more reason why agents and authors in India cannot expect huge advances because the advance is based on the MRP of the book. Debut fiction is by far the most price-sensitive genre and I have seen overpriced books in the genre get killed.

DS: When you suggest a manuscript to a publisher, do you visualise a book, how it should appear in print? What are you preferred books, in terms of shape and size and paper quality?

KG: I don’t visualise the book, but I do visualise the format, whether it should be hardback, high quality paperback or cheap paperback. Sometimes I have an image in my mind for the cover design. I have a fondness for big hardbacks with very readable fonts.

DS: Which publisher according to you put more efforts than others to produce books, which are good looking and of high quality?

KG: Aleph Book Company. However, most hardbacks produced by mainstream publishers are usually good looking and of high quality.

DS: The million-dollar question is in the literary landscape, who decides the taste? Who decides what book has the potential to be a bestseller?

KG: Earlier, it used to be the publisher or the editor, but now most decisions involve everyone from sales, production and marketing. There is huge interference from sales and marketing in the acquisitions process. While it can get extremely annoying at times, one has to understand that it is they who have to ultimately support and sell the book. On many occasions, sales and marketing departments have shot down my books despite unanimous approval from the editors.

A patient listener, advisor, manager and mentor rolled into one

What does a literary agent do exactly?

A good agent will not only find a good book and match it to the right publisher but will handhold the author throughout the process from signing a contract all the way to post-publication activities. He has to be a patient listener, advisor, manager and mentor rolled into one. It’s easy for me because I relate to all the highs, lows, doubts, anxieties, ego clashes, phases of self-importance and megalomania and so on, because I too possessed them in great abundance at one time.

How did you become a literary agent?

After a life-altering episode right after school, I gravitated towards writing. After sleepwalking through college, I started looking for publishing possibilities for my novel. At that time, there was just one Bangalore-based agency and a Delhi-based representative of a major foreign agent. In short, access to publishers was near-impossible.

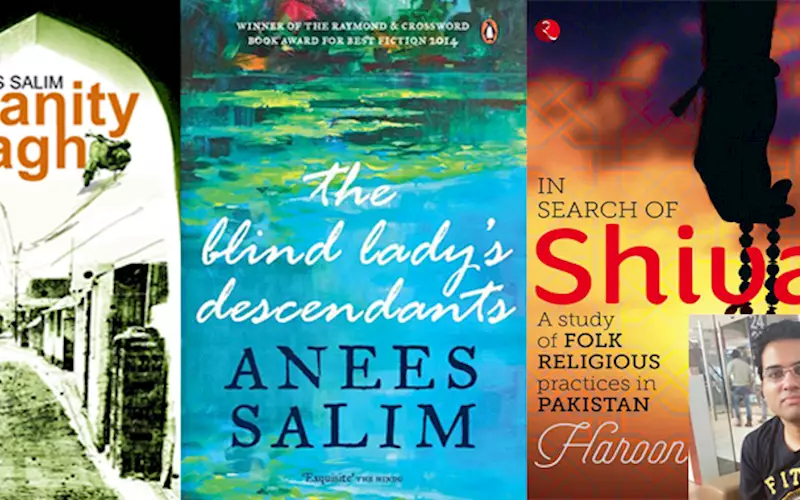

Several years of unemployment later, I joined an agency as an evaluator. Thereafter, I started working for JLF director Namita Gokhale as an assistant. It was she who told me that she saw me becoming an entrepreneur, but at that time branching out on my own seemed impossible because I was nobody in publishing. A few months later, I started my agency and editorial consultancy but found my first author Anees Salim after more than one year.

What do you look for in a manuscript, a good book or what a publisher may like?

It has to be a good book first and foremost, but whether or not it is marketable and will appeal to the publishers is also a major criterion for representation. Authors must realise that we are middlemen and have to change and adapt with the changing requirements of our buyers.

What kind of manuscripts are you looking at right now?

I think I am the only agent who looks at every single genre provided the book is good!

What advice would you give to a newcomer who wants to become a literary agent?

Frankly, I would not wish ‘agenting’ upon my worst enemy. It’s difficult, thankless and low paying. Also, we hardly have any real success stories in agenting in India. Many agencies started by well known publishing professionals have closed down or haven’t performed as per expectation. However, if you really want to give agenting a shot then make sure you have a sufficient financial cushion and a slightly more regular source of income. I have reached big volumes and a high turnover after years of hard work and single-minded devotion. Unless you have been an integral part of publishing or are from a family of publishers, establishing a foothold in this field would be very difficult. I succeeded partially because of my brief stint as a novelist. But then I am a major aberration in South Asian publishing!

Kanishka Gupta’s favourite books

I think Anees Salim’s Vanity Bagh, Ali Akbar Natiq’s What Will You Give For This Beauty, Sanjoy Chakravorty’s Promoter, Josy Joseph’s A Feast of Vultures, Faith Johnston’s Four Miles To Freedom, NS Inamdar’s Rau, Intizar Hussain’s The Sea Lies Ahead are all high quality print books.

For me, the font size and type is very important and should not detract from the reading experience. The next important criterion is the cover, followed by the paper quality and texture. Binding is important too.

See All

See All